2024 U.S. ELECTIONS RAPID RESEARCH BLOG

Predictable errors and delays that have been the focus of previous election rumors were present in the N.H. primary, but none of the allegations went viral.

By Mike Caulfield, Mert Can Bayar, and Ashlyn B. Aske

University of Washington

Center for an Informed Public

This is the third in an ongoing series of rapid research blog posts and rapid research analysis about the 2024 U.S. elections from the University of Washington’s Center for an Informed Public.

Many familiar election rumors began to emerge leading up to the results of New Hampshire’s primary on Tuesday night. There were concerns about downed machines in the city of Laconia’s Ward 2, echoing viral concerns from both the 2020 general election and Arizona’s 2022 general election. Near the end of the night, the town of Derry reportedly ran low on Republican ballots, which echoed viral concerns from Arizona’s 2022 primary. Other posts suggested that an unidentified “ten communities” were running out of ballots. Leading up to election day, posters on X shared lists of places where Trump’s name on the ballot appeared on or around the ballot fold, part of a conspiracy theory based on a misinterpretation of an error in Windham, New Hampshire in 2020 that has been wrongly cited by former President Trump as proof of election fraud. Such tweets implored other conservatives to keep an eye on the 14 wards (out of hundreds in New Hampshire) that were said to have Trump’s name in “slot position 15” on the ballot.

Yet, with Trump obtaining a comfortable double-digit margin, none of these allegations of a conspiracy of election workers to “fix” an election went viral. While our search of X , formerly known as Twitter, is not comprehensive, we found most of such posts attained a few hundred views or less.

Similarly, the predictable errors and delays that have been the focus of election rumors in the past were present. Despite the best efforts of election workers in New Hampshire, only 85% of the vote was in by midnight. Since the map does not update past a certain point, if you looked on the New York Times map the following morning, you’d find only one Republican vote in the town of Fitzwilliam had been recorded, despite the Democratic votes having been tallied. We found no election rumors about either of these issues (which is as it should be — every election has delays or odd reporting issues).

Instead, the most prominent conspiracy theory we observed about officials “fixing” the election was about the Democratic ticket. The tweet below, from a conservative account referencing an unnamed source, got 4.5 million views:

SOURCE: Rep. Dean Phillips received almost twice as many votes as Biden did in the New Hampshire primary. The Democrat Party, in an effort not to embarrass the president, ‘found’ 50,000+ write in votes for Biden to give him the ‘win’. This follows Dean’s claim that his party is “Delusional Right Now.”

That tweet became prominent enough that Democratic candidate Dean Phillips explicitly rejected its claims from his own account:

This is shameful and absolutely untrue. The State of New Hampshire manages its elections with great integrity and efficiency, and Joe Biden won the NH Democratic primary election last evening fair and square.

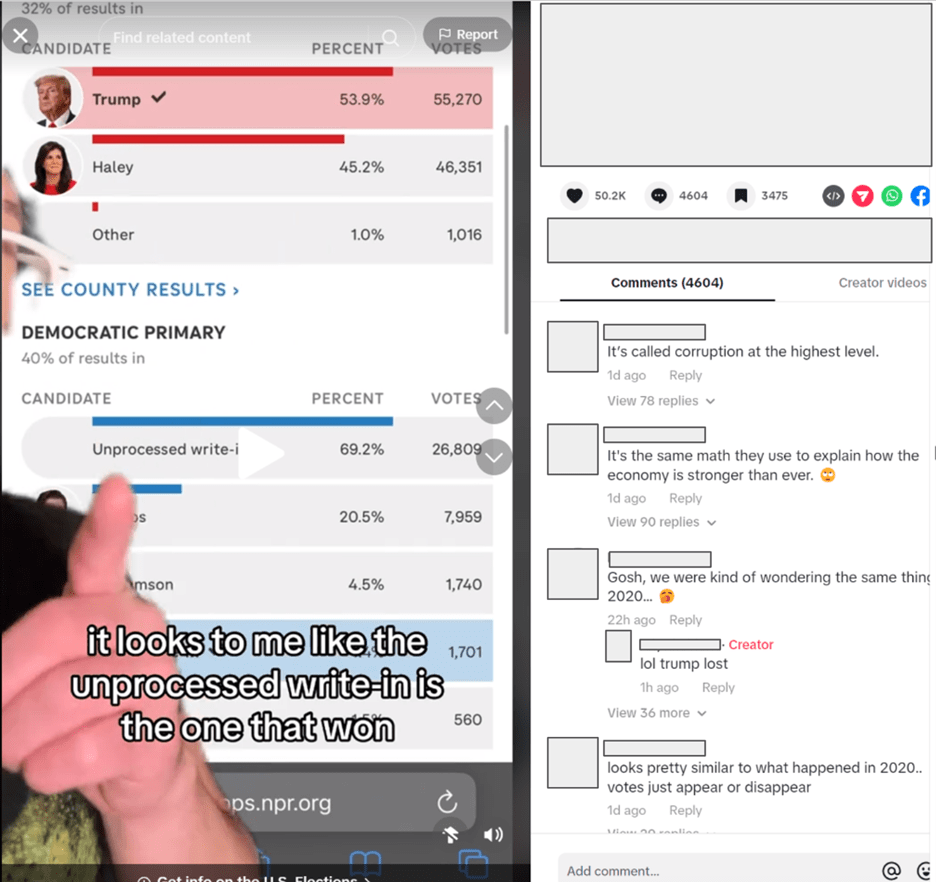

In other cases, related claims emerged on the political left but found amplification on the right. On TikTok, a user on the left posted a video claiming that “unprocessed write-ins” — not Joe Biden — were winning the primary election. The implication was that a campaign to write in “ceasefire” might be beating Biden by a substantial margin and that National Public Radio was calling the race too early for Biden. The poster found himself debating in the comments, with right-wing commenters citing this as evidence that Democrats were stealing the current election “similar to what happened in 2020.”

That video got over 700,000 views. An hour later, a subsequent video where the poster admits that NPR was right — that the unprocessed write-ins did resolve for Biden — received just 2,000 views.

The type of conspiracy theory referenced in both the viral tweet and in the reactions to the TikTok video is one familiar to researchers of election rumors. According to the baseless theory, Democrats often wait to see how much they are going to lose an election by, then “find” fake votes to add to the totals during election night. Different mechanisms for adding such votes to the count are proposed, such as “suitcases of ballots” or “hacked machines,” and graphs of sudden shifts in vote share are said to be evidence of the “steal” in action.

The success of content referencing this trope is unsurprising, given its centrality to 2020 stolen election mythologies. Yet in other ways the focus on this issue is striking. Before beginning this project, we made an extensive study of rumors from primary contests over the past decade, and found that in the past primary cycle rumor and conspiracy theory was most often directed at one’s primary opponents or one’s own party establishment. This makes the recent primary rumors of the right somewhat unusual. The two major rumors of the Republican primary cycle so far — rumors about Democrats “infiltrating” party contests and rumors about Biden “fixing” his election — target not intra-party Republicans but extra-party Democrats.

The relative popularity of content targeting the Democrats may be a sign of an unusual election. With no viable Republican opponents to target, rumors about supposed Democratic primary malfeasance among those on the political right may help to maintain false beliefs about the general election of 2020 and serve to justify fears about the general election of 2024. For this group of narrative-builders, the general election has already begun. Despite the relative “quiet” of intra-party rumor during this primary, the engagement with these extra-party narratives, 10 months before the general election, signal a group of supporters eager — and perhaps impatient — to rerun the claims and tropes of the 2020 election.

A Note on Terminology: Following a common practice in academic scholarship, we refer to the different elements of X (tweets, retweets, likes, follows) by the terms used in the community itself. Likewise, we use terms like “news twitter” and “crisis twitter,” both lower case, as the common names used on X to refer to these communities or discourse subgroups. When referring to the platform itself or associated policies, we use the term “X,” the legal name of the platform.

- Mike Caulfield is a Center for an Informed Public research scientist; Mert Can Bayar is a CIP postdoctoral scholar; and Ashlyn B. Aske is a CIP graduate research assistant.

- Photo at top: Former President Trump at a campaign rally in Rochester, New Hampshire on January 21, 2024. Photo by Liam Enea / Flickr via CC BY-SA 2.0 DEED

- For additional updates from the Center for an Informed Public’s rapid research from the 2024 U.S. election cycle, follow Mike Caulfield on Bluesky, the CIP on Mastodon and LinkedIn.