2024 U.S. ELECTIONS RAPID RESEARCH BLOG

We examine the origins, content, and social media spread of a misleading video that connects U.S. border narratives to concerns with election integrity

By Mert Can Bayar, Ashlyn B. Aske, Nina Lutz, Joseph S. Schafer, Stephen Prochaska, and Kate Starbird

Center for an Informed Public

University of Washington

This is part of an ongoing series of rapid research blog posts and rapid research analysis about the 2024 U.S. elections from the University of Washington’s Center for an Informed Public.

On February 5, 2024, as the battle for the U.S. presidency began to ramp up, an aspirational influencer posted an election-themed video to several social media platforms. The short-form video, which eventually garnered millions of views, featured a “man on the street” interview with recent migrants. The original interview was conducted in Spanish, but the video had English subtitles. Its message? Migrants were planning to vote, illegally, for Joe Biden.

The video struck a chord that resonated with two prominent political narratives: one around the “border crisis” and the other around persistent (and misleading) claims of “rigged elections.”

In the last few years, the number of newly arriving immigrants at the U.S. southern border has rapidly increased and encounters with federal officials at the border have soared. Underlying these statistics are a record number of migrant encounters at the U.S.-Mexico land border and a record number of asylum cases, which are straining existing systems, resulting in cascades of impacts across communities, both at the border and beyond.

This complex situation has been broadly characterized as a “crisis” in mainstream and partisan media outlets. Conservative political pundits, politicians, and advocacy organizations have seized upon the situation to criticize President Biden’s leadership, while Democrats have called out Republican congressional leadership for blocking efforts to address it.

The crisis at the border provides opportunity and fuel for other political narratives, including the persistent and false narrative of “rigged elections.” Rumors about election fraud have long been a feature of U.S. elections, but they grew pervasive during the 2020 U.S. election, especially among supporters of then-President Trump, who actively promoted several false allegations. Heading into the 2024 U.S. election season, surveys have suggested that 62% of Republican voters believe that there was systematic fraud in the 2020 election. Many remain concerned about the integrity of U.S. elections. Allegations of rigged elections cite several different mechanisms, from discarded mail-in ballots to machines switching votes to election official corruption. One set of claims focuses on the concept of “non-citizen voting” to suggest that large numbers of immigrants vote illegally in U.S. elections. One rather provocative allegation — which echoes the “Great Replacement” conspiracy theory — is that Democrats intentionally create “open borders” so that they can “import voters” to win elections by diluting the vote of current citizens.

To better understand how these allegations (and political narratives more generally) take shape and move across our information ecosystem, here we present a multi-dimensional analysis — across source, content, and spread — of a single misleading video that connects the border crisis to concerns with election integrity. We first provide background on previous claims around “non-citizen voting” in U.S. elections. Next, we describe the video and demonstrate how it misleads through selective cuts and incomplete subtitles. Then, we show how the video spread across social media platforms — with help from a set of “new elite” influencers on Twitter/X. Finally, we explore the history of the video’s producer and demonstrate how he adapted his content to attract an audience that rewarded him for resonating with these political narratives. We conclude with recommendations for social media users and journalists to help us recognize misleading content, in part by tuning into the frames we use to interpret evidence.

Context: Rumors about non-citizen voting in U.S. elections

Non-citizen voting has long been a contentious issue in the United States. Laws around voting rights for non-citizens have shifted throughout history, often becoming more restrictive after large influxes of immigration. Most recently, in 1996, Congress passed a law prohibiting non-citizens from voting in federal elections. While that federal law remains in place, a small number of U.S. cities and counties have passed laws allowing non-citizen residents to vote in some local elections.

Rumors and false allegations around non-citizen voting are also not new. After the 2016 election, in an effort to downplay the fact that he had received fewer votes overall, President-elect Trump claimed that millions of immigrants had voted illegally for Hillary Clinton. Claims of non-citizen voting were also levied as part of the “rigged election” allegations in 2020 and 2022.

In 2022, our research team examined two distinct rumors about non-citizen voting in the midterm elections. The first deceptively framed a local law that would have allowed non-citizen residents to vote in local elections as enabling non-citizens to vote in state and federal elections. The second misleadingly suggested that a U.S. Department of Justice lawsuit aimed at protecting citizens’ rights to register to vote without undue burden was an attempt to enable non-citizen voting. Therefore, the lawsuit was interpreted as a Democrat-led effort to facilitate fraudulent voting by non-citizen voters.

So far, in the 2024 election season, much of the non-citizen voting discourse has converged around the narrative that Democrats intentionally support “open border” policies so that they can “import” immigrants to help them win elections — by both legal and illegal means. Partisan media outlets, influencers, and everyday social media users often frame and/or interpret the “border crisis” as an effort to disenfranchise U.S. citizens by diluting or drowning out their votes. In the following sections, we analyze a recently viral video and its spread across social media platforms, including its interaction with influencers, to demonstrate some of these dynamics.

The ‘Migrants for Biden 2024’ video

The “Migrants for Biden 2024” video was posted by its original creator[1] to at least four platforms (YouTube, TikTok, Instagram, and X) in slightly different forms on February 5, 2024. Below is a screenshot of his X post introducing the video:

Figure 1. Screenshots of the content creator posting his video to X.

The 22-second video features three distinct scenes where a young man approaches different individuals for interviews. (The young man is featured in many other videos associated with the social media accounts that initially posted this video, so we assume he is the owner and primary content creator for these accounts.) He speaks his questions into a red microphone, which he then extends towards the person answering. This “man-on-the-street” interview video style is popular on TikTok and other video-based social media platforms. Many of the content creator’s other videos on TikTok and Instagram feature a similar format.

On Instagram and X, the text “Migrants talk about the 2024 election” is overlaid at the top of the video frame, leading the viewer to conclude that the interviewees are migrants. The video includes several different frames showing different angles of what appears to be the same parking lot. In most clips, the content creator only addresses one other speaker, but the initial clip shows a conversation with a group of four others. He interacts with the “migrant” interviewees very neutrally. His tone of voice, body language, and facial expressions seem neither confrontational nor particularly friendly or sympathetic. The interviewees seem relatively at ease in response to his presence — one person can be seen sitting on a raised curb as the interviewer converses with them while standing.

There is substantial background noise throughout the video, including sounds of other people talking at times. The interviewees’ voices are often hard to hear due to poor sound quality and the microphone being held at a distance. Combined with the video’s production quality, the interviewer’s informal style, dress, and youth give the video a sense of authenticity often found in citizen journalism (as contrasted with professional journalism).

The interview — and, therefore, the entire audio of the video — is in Spanish. However, the content creator overlaid English-language subtitles across the bottom of the video frame. These subtitles seem to align with the audio and are implied to be translations of the content.

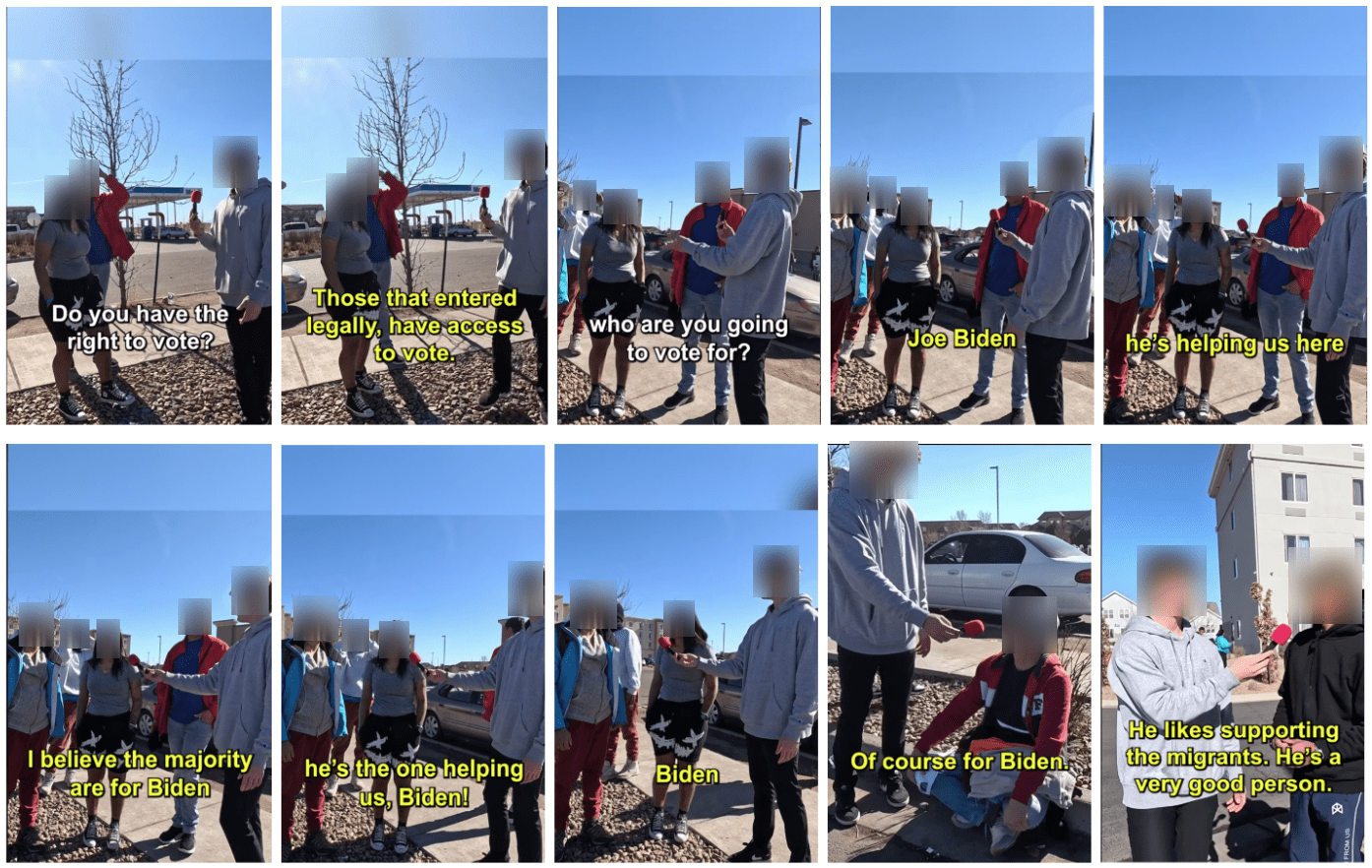

Figure 2. Screenshots of the short-form video. The 22-second edited video shows an interviewee answering the question “Do you have the right to vote?” and several other interviewees answering the question “Who are you going to vote for?”

Figure 2. Screenshots of the short-form video. The 22-second edited video shows an interviewee answering the question “Do you have the right to vote?” and several other interviewees answering the question “Who are you going to vote for?”

Through these prominent English subtitles, the video gives the impression that the undocumented immigrants plan to vote for Joe Biden. The content creator alludes to that framing in his X post introducing the video, writing: “Confirmed! Migrants for Biden 2024.” Comments on social media posts featuring the video demonstrate audiences interpreting the video as evidence of “rigged elections.”

Contextual edits and incomplete translations: How the video misleads

A close analysis of several versions of this video reveals this framing and these interpretations to be false, resulting from misleading editing — including how the video was cut and how the subtitles were selected and translated from the original interviews.

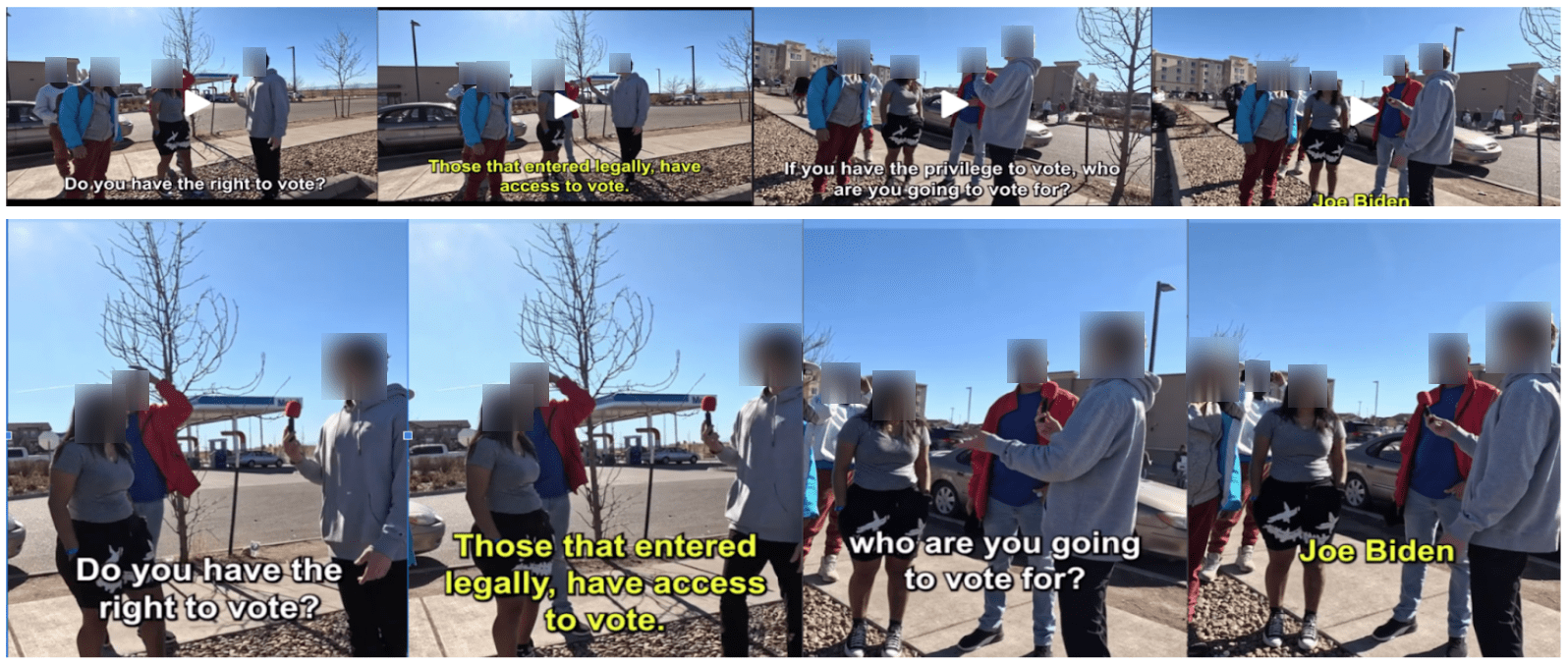

This short-form video described above was posted in similar versions to Instagram, X, and TikTok (in the afternoon on February 5). Its content, however, was cut from a much longer video posted to YouTube a few hours earlier. Here is a comparison between the two versions:

Figure 3. Screenshots from the two versions of the view. The top four screenshots are taken from the longer video, while the bottom four screenshots are taken from the short video. The content creator uploaded the longer video to his YouTube channel. A few hours after its appearance on YouTube, he uploaded the short (edited) video to their Twitter, Instagram, and TikTok accounts.

The edits eliminated key context from the questions asked to the interviewees. For instance, in the YouTube video, the content creator asks the interviewees, “If you could vote, who would you vote for?” and “If you have the privilege to vote, who are you going to vote for?” in Spanish and provides translations of both questions in English subtitles. However, the short-form version cut one of the questions entirely and omitted the conditionality of the remaining voting question. (Figure 4 shows how Q2A and Q3 in the original are edited to become Q2B in the short-form video, obscuring the conditionality in the interviewer’s questions). Because of this editorial distinction, viewers of the short-form video may come to the incorrect interpretation that these migrants believe they have the right to vote and intend to do so.

| The Original Version on YouTube | The Short-Form Version on Twitter/X, TikTok, and Instagram |

| Q1A: Do you have the right to vote A1: Those that entered legally have access to the vote. Q2A: If you have the privilege to vote, who are you going to vote for? A2: Joe Biden. He’s helping us here. A1: I think the majority are for Biden A2: He’s the one helping us, Biden A3: Biden Q3: And if you could vote, who would you vote for? A4: Of course for Biden |

Q1B: Do you have the right to vote A1: Those that entered legally have access to the vote. Q2B: who are you going to vote for? A2: Joe Biden. He’s helping us here. A1: I think the majority are for Biden A2: He’s the one helping us, Biden A3: Biden A4: Of course for Biden |

Table 1. Comparison of Subtitles between the Original, Long-Form Video on YouTube and the Edited, Short-Form Videos on X, TikTok, and Instagram. The conversations between the content creator and interviewees in the original (longer) video on YouTube are displayed on the left. Highlighted questions: Q2A and Q3 show the conditionality of the voting question in this version. Q2B on the right shows how the edited version removes the conditionality and displays the voting question without context.

Additionally, some of the other translations in the video may not be completely accurate. With the help of native Spanish speakers, we attempted to check the translations, both in the original and the short-form video. Due to poor audio quality, they were difficult to confirm in places. In one case, where the migrant in the red sweatshirt responded to the question about whether immigrants have the right to vote, our research determined that the subtitles failed to reflect that the person was unsure in his response, possibly trying to clarify the question by repeating it back to the interviewer.

Cross-posting and elite-boosting: How the video spread

The video’s creator used a multi-platform strategy to share his video. Table 1 shows the time he posted his video to each platform and the number of views his video received (as of February 25, 2024). Eventually, the video would garner millions of views across different platforms. Due to data transparency limitations, we are unable to track precisely when the video accumulated views across the different platforms. However, a rough analysis of comments on Instagram and YouTube suggests that much of the long-form (YouTube) video’s engagement occurred immediately after the original was posted (on February 5), but most of the engagement on the short-form video (which contained the misleading edits described above) occurred on February 7 and 8, more than two days after it was initially posted.

| Platform | Upload Time (on Feb. 5, 2024) | Number of Views (in platform)[2] |

| YouTube (long version) | 12:02 p.m. PST | 220K views |

| 2:15 p.m. PST | 4.2M views | |

| X (short version) | 2:20 p.m. PST | 145.2K views |

| TikTok (short version) | 4:25 p.m. PST | 48.4K views |

Table 2: Original posts by the content creator introducing the video across platforms. The videos mentioned above are the videos by the content creator. It does not include the posts by other influencers mentioned in the report.

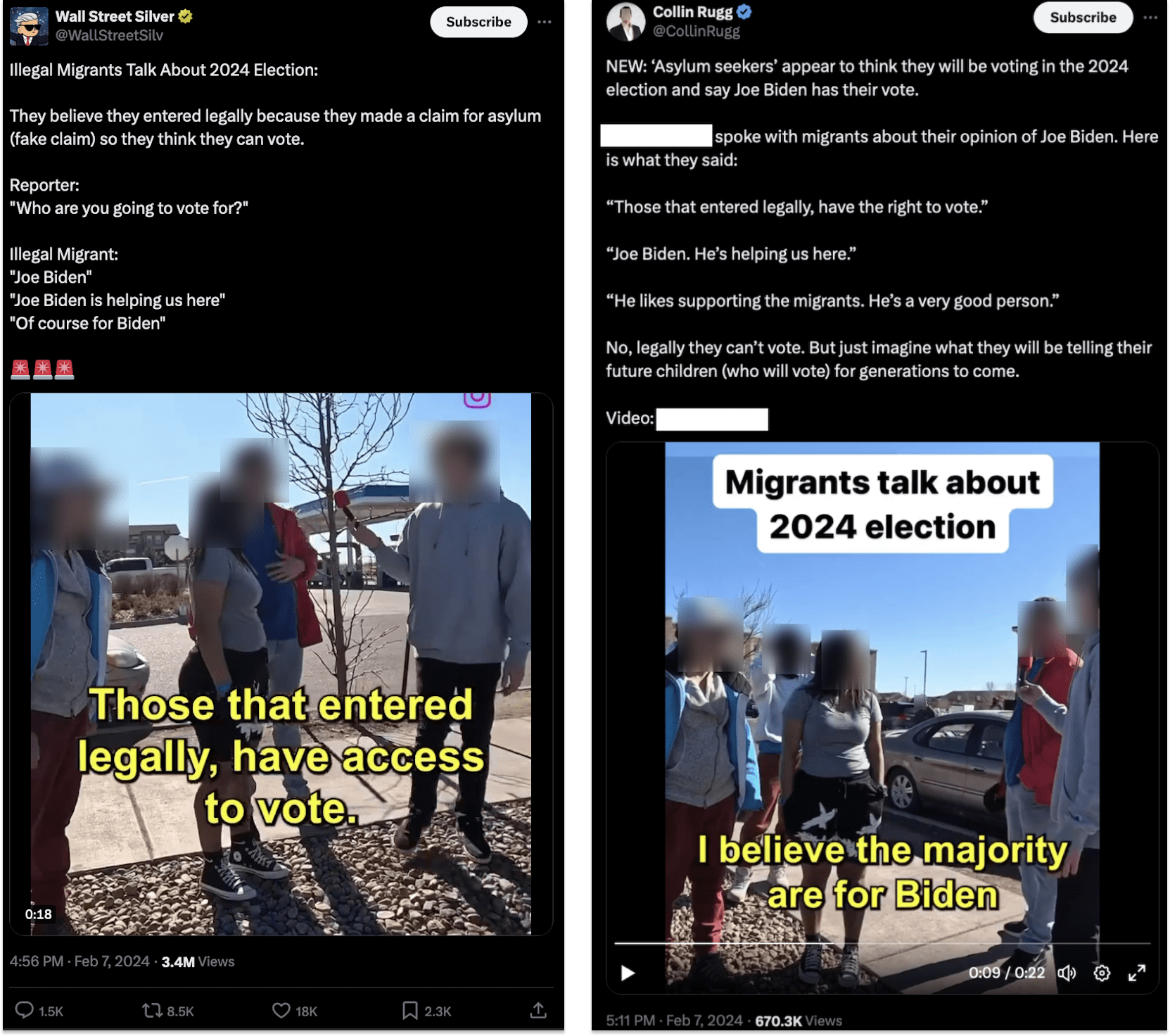

The short-form video took off and eventually garnered millions of views with the help of larger audience accounts that boosted the video and spotlighted its creator. It first began to gain traction on Instagram on February 7 between 1 and 2 p.m. (PST). A few hours later, at 4:56 p.m., perhaps seeking to leverage the content to garner attention for itself, a gold-check account called “Wall Street Silver” (@WallStreetSilv) posted a copy of the Instagram version of the video to X. (Gold checkmarks reflect participation in X’s Verified Organization program, which organizations and brands can purchase.) @WallStreetSilv’s post reflected and reinforced the misleading framing that the migrants in the video believe that they can vote:

Figure 4. Highly viewed posts by high-following accounts that reintroduced the video on X.

@WallStreetSilv’s account has over a million followers on X. His tweet, which eventually received more than 3 million views, quickly drew the attention of other high-following accounts. Less than 15 minutes later, another X influencer with a massive audience (at 927k followers as of March 12, 2024), @CollinRugg, posted his own tweet featuring the video as it was initially posted on X.

In previous research, our team determined @CollinRugg to be part of a group of “new elites” on X. These accounts have grown influential in political discourse since Elon Musk took ownership of Twitter and as the platform shifted to become X. In our original reporting, we theorized that one factor in the rise of the “new elites” is that many have received direct engagement (likes, comments, reposts, or public mentions) from Musk. That dynamic occurred in this case as well. About 30 minutes after @CollinRugg’s post, Elon Musk (@elonmusk) replied to the tweet with an exclamation point. Later, Rugg responded, “It’s all part of the plan,” a nod to the narrative that Biden’s border policies are intended to increase the number of Democratic voters.

As the video began to go viral on X, its creator also began to gain attention. @WallStreetSilv added a comment to his post crediting the video’s creator and directing his audience to the creator’s X account. Collin Rugg’s post explicitly called out and credited the video’s creator as well. These boosts provided exponentially more visibility and a new genre of audience for the video’s content creator.

After his “Migrants for Biden 2024” began to spread widely, several influential accounts on X started to share other content produced by the creator — a dynamic that echoed across platforms and the broader media ecosystem. Wall Street Silver continued posting about the creator’s videos, including one that Musk replied to with his signature-style exclamation point. On February 9, Fox News featured the content creator on the Jesse Watters Primetime show — referring to him as an “investigative video journalist.” Over the next few weeks, other influential accounts would post additional videos by the same creator featuring interviews with migrants. Musk would reply to at least one of those with another exclamation point. Repeatedly promoted — or “spotlighted” — by these established influencers, the video’s content creator was on his way to becoming an influencer himself.

An aspiring influencer shifts to interviewing immigrants

The rising influencer rapidly gained followers across his social media accounts. This burst of attention may have been unexpected, but it was also the culmination of a years-long effort by the content creator to build an audience on social media — and a recent change in his approach. He has been active on X since 2017, YouTube and Instagram since 2018, and TikTok since 2019. Analysis of his past content production reveals a distinct shift in late 2023 to posting about immigration and provides insight into the broader dynamics of political discourse and “influence” online.

The creator’s early content (2017–2021) mostly focused on pranks, pop culture, stunt videos, and “sneaking” into concerts and similar events. The videos seem designed to gain the attention of other young people. A few of his posts had obliquely political content, such as one YouTube video in early 2020 interviewing people at a Bernie Sanders rally, a prank video in late 2020 pretending to be a “mask enforcement patrol,” and most notably, a video interviewing attendees of the January 6, 2021, protests at the U.S. Capitol.

Between 2021 and 2023, the creator stopped producing social media content, explaining to his audience that he was doing missionary work in Chile. His content took on a different style and tone when he returned to social media in November 2023. Initially, he posted two videos featuring “man-on-the-street” interviews with college students similar to his previous style, but soon he shifted to repeatedly producing videos about immigration, often featuring Spanish-language interviews with migrants (accompanied by English-language subtitles and narration). Our analysis suggests this shift may have been partially motivated by higher levels of engagement in his first immigration-focused video.

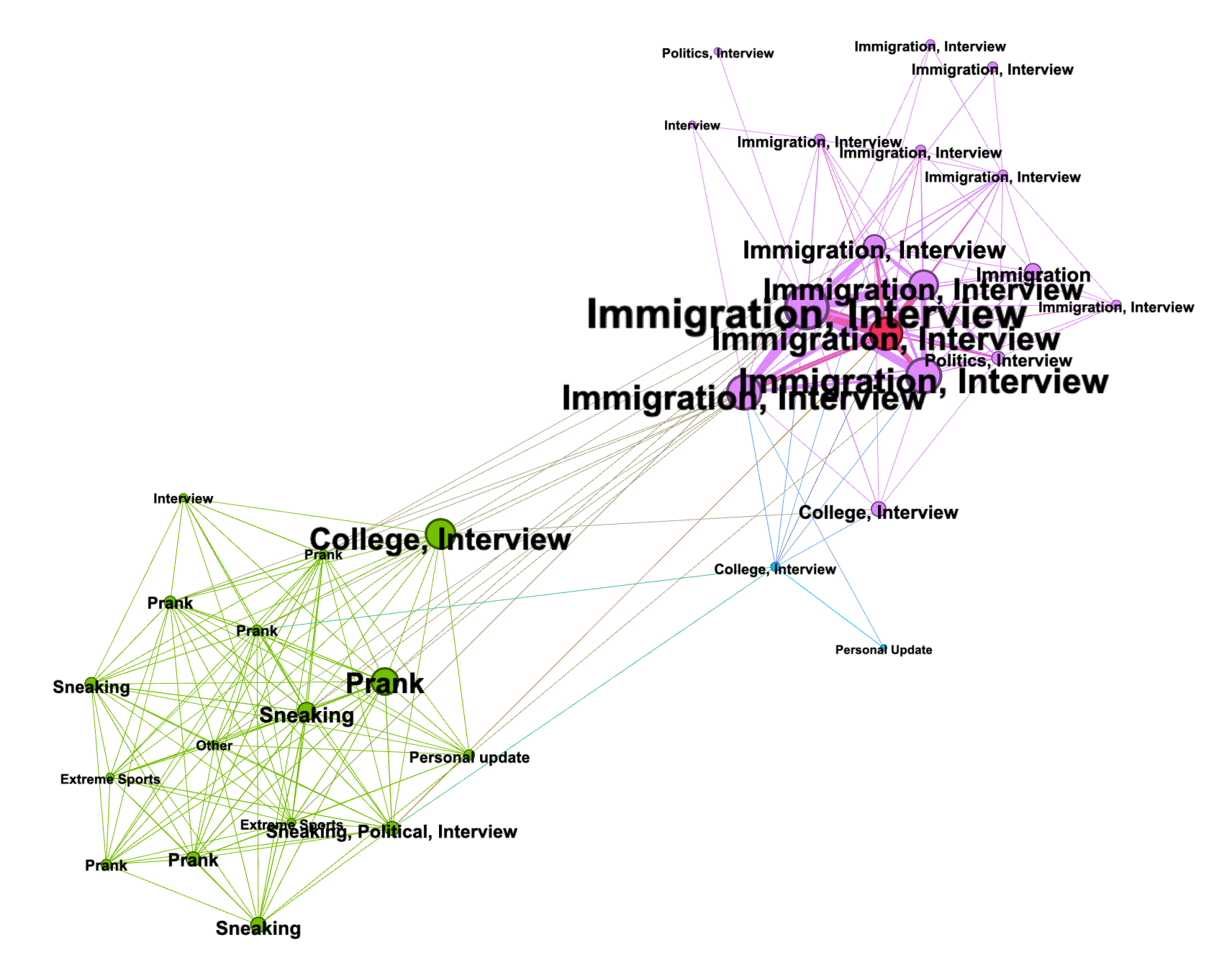

The graph below, a shared audience projection of this creator’s YouTube videos and YouTube shorts, demonstrates the profound shift in his content production. Each node on the graph is a YouTube video. An edge connects two videos when at least three YouTube users commented on both videos. The graph reveals how the creator’s more recent content (primarily in pink) differs drastically from his earlier content (primarily in green) and how his videos featuring interviews with immigrants receive engagement from a very different (and significantly larger) audience.

Figure 5: Shared Audience Projection of the Content Creator’s YouTube Posts. This network graph shows the creator’s YouTube video posts since 2021 (both full-length videos and YouTube Shorts), connected if videos have at least three shared commenters between them. Each video is labeled with its genre of content, which had common themes of pranks, extreme sports, and “sneaking” into various events, concerts, etc., in the creator’s earlier content, and particularly in their later content talking about immigration and politics-related topics using “man-on-the-street” interview formats, labeled as “Interview” above. Nodes are sized by the number of views the video received. Visualization was created in Gephi using modularity clustering and the ForceAtlas2 algorithm. The video this blog post examines is highlighted in red but is a part of the ordinarily pink cluster.

Figure 5: Shared Audience Projection of the Content Creator’s YouTube Posts. This network graph shows the creator’s YouTube video posts since 2021 (both full-length videos and YouTube Shorts), connected if videos have at least three shared commenters between them. Each video is labeled with its genre of content, which had common themes of pranks, extreme sports, and “sneaking” into various events, concerts, etc., in the creator’s earlier content, and particularly in their later content talking about immigration and politics-related topics using “man-on-the-street” interview formats, labeled as “Interview” above. Nodes are sized by the number of views the video received. Visualization was created in Gephi using modularity clustering and the ForceAtlas2 algorithm. The video this blog post examines is highlighted in red but is a part of the ordinarily pink cluster.

‘News broker’ influencers spotlight content creators who produce evidence to fit prevailing frames

The story of this video and its creator reveals two related dynamics of the social media-enabled attention economy. The first speaks to the always-evolving structure of online environments, where information flows are increasingly mediated by a type of social media influencer (a high-following account) that our colleague Mike Caulfield recently described as a “news broker.” This case underscores the role of news brokers in directing attention from their audiences onto the content (and accounts) of smaller accounts — setting them on a pathway to rise to influencer status themselves. Our research team has previously referred to this dynamic as spotlighting.

The second dynamic helps explain what kinds of content will likely get “spotlighted” in this way. In the video we examine, the aspiring influencer who has been experimenting with different formats and topics suddenly strikes attentional gold. His content gets boosted by massive influencers, receives engagement from the owner of X, and soon reaches millions of viewers. Why?

One explanation is that he managed to find a recipe — in both the format of his videos and the content he produced — that resonated with existing “frames” within the shared audiences of those more established influencers. The creator’s relaxed, man-on-the-street style and his ability to conduct Spanish-language interviews contribute to a sense of authenticity, likability, and perhaps credibility among his newfound audience. His recent content, especially the “Migrants for Biden 2024” video, resonates with existing rhetoric around “non-citizen voting” and with prevailing frames among conservatives that see elections as “rigged” and rising immigration in the U.S. as a “crisis.”

Previous research explains how the spread of false and misleading claims about the 2020 election took shape through a participatory process where (1) elites in politics and media set the frame of a “rigged election”; (2) online audiences produced “evidence” to fit that frame, often by misinterpreting ambiguous and/or uncertain events (such as Sharpies bleeding through ballots or shifts in vote counts) as evidence of fraud; (3) and a class of social media influencers that we have recently termed “news brokers” played the role of helping to find and amplify evidence that fit the frames. This dynamic is very similar to the events in this case, where the aspiring “content-creator” influencer produced novel evidence in the form of selectively edited interviews with migrants, and a group of “news broker” influencers promoted that evidence to fit their frames.

| Role | Description |

| Frame Setters | Elites in politics and media build and promote frames through which others interpret evidence and events in the world. |

| News Brokers | A type of social media influencer that works to find and amplify (or “spotlight”) evidence to fit prevailing frames. |

| Content Creators | A type of social media user that produces content that serves as “evidence” that resonates with prevailing frames |

Table 3: Types of influencers that work to build, support, and reinforce political frames.

This is likely a winning strategy for creators trying to garner attention in the current attention economy. It incentivizes them to create certain kinds of content and rewards them when they do. And we are likely to continue to see similar dynamics — of elites setting frames, content creators producing evidence to fit those frames, and news brokers finding and amplifying that evidence, reinforcing those frames. Some of this evidence will be legitimate evidence accurately portrayed and interpreted. But in the coming months, we are also likely to see misinterpreted, mischaracterized, manipulated, and even manufactured evidence, spawning false rumors about immigration and the 2024 election.

Conclusions and Recommendations

This blog post tells the story of how a single video and its creator captured the attention of a massive audience by tapping into prominent frames of a “border crisis” and a “rigged election.” Through close analysis of the content, we show how short-form video, in particular, can mislead through selective edits and incomplete subtitles. Through cross-platform analysis of the video’s source and spread, we reveal how news-brokering political influencers can raise the profile of creators who produce content that aligns with their preferred frames.

The content producer’s account history suggests that he has experimented with different formats and topics to gain attention, eventually finding a recipe — producing short-form video content featuring “man on the street” interviews with migrants — that is attracting significant engagement from a large audience. We expect other aspiring “influencers” to adopt a similar approach in the coming months.

We also expect to see more motivated sharing of rumors and misleading content at the intersection of the border crisis and the election, including false claims that deceptively connect immigration to election fraud.

Extending from these findings, we have recommendations for social media users to protect themselves from being misled, especially by short-form video content, and for journalists covering issues — like immigration and elections — where strategic frames are generated, promoted, and reinforced through evidence production, news brokership, and the involvement of influencers on social (and traditional) media.

Recommendations for social media users

Understand how we can be misled through frames as well as evidence.

- Political influence works both by promoting specific frames and by selectively amplifying evidence that fits, or appears to fit, those frames. Experts in media literacy teach us to tune into the frames conveyed within the content we encounter — whether in traditional or social media. But it can also be valuable to tune into the frames that we bring to events and issues we encounter in the world because those frames shape how we select and interpret “evidence.”

- We are more likely to be misled by deceptive content when it aligns with our preferred frames. Swapping out our preferred frame for an alternative one may help us see evidence in a different way and perhaps recognize where we may be misinterpreting things — or when someone may be misleading us.

- It is also important to recognize how evidence reinforces frames. When we encounter new evidence that fits an existing frame, that frame grows stronger in our minds. However, when we later learn that the evidence was false or falsely interpreted, it may take significant work to reverse its impact on the strength of our frame. Try to remember to do that work!

Become savvier about viewing and vetting short-form video content.

- Tune into the scene switches and production cuts to notice where something that could affect your interpretation might have been selectively removed from or reordered with the video.

- Pay attention to how the subtitles align with the audio and where the audio quality makes it difficult to assess that alignment.

- If the original video is in another language, be wary that the translation may be imperfect, which could lead to accidental misinterpretation or enable intentional mischaracterization of the content.

Recommendations for journalists

Tune in to learn how journalists can unwittingly strengthen politically constructed frames by further amplifying content produced to fit those frames.

- In recent years, journalism has begun to leverage social media posts as content for their coverage. Though a valuable means of hearing from diverse voices and surfacing first-hand accounts of events, this practice is also vulnerable to manipulation by the same dynamics described here. When featuring social media content, tune into — and consider explaining to your audiences — how the content that often rises to the surface and becomes visible to you (and them) may have been amplified by politically motivated audiences and influencers working to selectively promote “evidence” that supports their frames selectively. (This resource can be helpful for journalists working to unwind the provenance of specific content.)

- Tune in as well to where that “evidence” may be misleading, either misinterpreted or misrepresented by its author, who may be incentivized to produce content that resonates with specific frames.

More generally, when working on the topic of immigration, it may be valuable to look to resources from culturally specific media organizations, such as this guide for journalists covering Latino communities from Factchequeado.

Footnotes

-

[1] We anonymize account names to protect the identity of accounts that may have a reasonable expectation of privacy. However, we do not anonymize public figures, professional journalists, verified accounts, and accounts that have massive online followings (>250k followers).

-

[2] Each platform independently calculates its views (and other metrics), and may use different methods. As a result, views across platforms may not be directly comparable (e.g., the creator having ~30x views on Instagram compared to X doesn’t necessarily mean that the Instagram video was exactly 30x as influential).

- Mert Can Bayar is a CIP postdoctoral scholar based in the UW Department of Human-Centered Design & Engineering.

- Ashlyn B. Aske is a CIP graduate research assistant and a Master of Jurisprudence student at the UW School of Law.

- Nina Lutz is a CIP doctoral research assistant based in the UW Department of Human Centered Design & Engineering.

- Joseph S. Schafer is a CIP doctoral research assistant based in the UW Department of Human Centered Design & Engineering.

- Stephen Prochaska is a CIP doctoral research assistant based in the UW Information School.

- Kate Starbird, a UW Human Centered Design & Engineering associate professor, is a CIP co-founder and director.

- Photo at top: The U.S.-Mexico border near Sunland, New Mexico by Anne Adrian / Flickr via CC BY 2.0 DEED