2024 U.S. ELECTIONS RAPID RESEARCH BLOG

Many of the small issues that have previously been the foundation of wide-scale groundless speculation went largely unnoticed online.

By Mike Caulfield, Mert Can Bayar, and Ashlyn B. Aske

University of Washington

Center for an Informed Public

This is the second in an ongoing series of rapid research blog posts and rapid research analysis about the 2024 U.S. elections from the University of Washington’s Center for an Informed Public.

The Iowa Caucus was called rather quickly on Monday night, with many news organizations declaring Donald Trump the winner less than a half hour after the 7 p.m. CST start of the caucus.

We tracked election rumors throughout the lead-up to the caucus and the caucus itself. Leading up to the announcement of results we saw a small number of rumors — and a few classic “fake news” items. On Friday, there was a flurry of concern about a consulting organization called Red Oak Strategic, and later, a related concern about a caucus app being used to report the results. There were also a number of fully fabricated assertions, like the claim that Republican candidates Nikki Haley and Ron DeSantis were working with the Democratic National Committee to buy votes.

Conversely, after the election was called for Trump, our search of X found no election integrity rumors at all. This is unusual. Unlike for previous Iowa caucuses, we found no complaints about the handling of voting slips, speculation about odd processes, “suspicious” app failures, deception about candidate status.

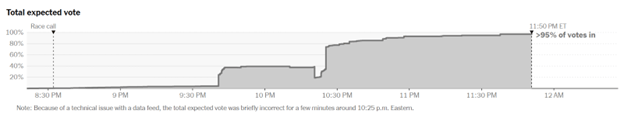

Often our work focuses on the small errors, delays, and anomalies that wrongly get turned into speculation about a lack of election integrity. In Iowa, the most interesting pattern was the reverse. Many of the small issues that have been the foundation of wide-scale groundless speculation in recent primaries and general elections went largely unnoticed online. For instance, the returns of the caucus were not fully reported by the morning — even at noon the day after the election news outlets were still waiting on some precincts. Such delays have been the foundation of conspiracy theories before, but with Trump in a comfortable lead they were not remarked on. Even more notably, we saw real-time returns shift late in the evening, with a sudden drop in percentage of returns occurring around 10:30 p.m., then jumping up, due to a data issue at The New York Times. While simply the result of an issue with a data feed, this sort of sudden spike was central to extensive and widespread conspiracy theories in both 2020 and 2022, where such spikes were (wrongly) claimed to be evidence of an influx of invalid, fabricated votes.

And yet, we didn’t find any rumors or conspiracy theories about Monday night’s sudden drop and spike.

Smaller issues displayed similar patterns. A video of one location storing filled-out vote slips in popcorn buckets as containers emerged, a point of contention in previous caucuses. In our research on prevalent caucus rumor of 2016 we found many people expressing disbelief online that such a process could be reliable. And as recently as 2022, online audiences following the Arizona gubernatorial race wrongly suggested the use of specialized security duffel bags might violate chain of custody rules. However, in this case, those commenting on the popcorn bins tended to (correctly) see their use as part of a reliable process, even suggesting this might be a better way to run the general election.

The lack of concern about these matters is probably appropriate. Vote counts often stall with a few percent outstanding, as a small amount of tougher reporting issues take time to work out. The data glitch (sudden drop and spike in the vote count at around 10:20 p.m. EST) at The New York Times was just a data glitch, not evidence of a conspiracy, or of a flood of mysterious ballots. And with the popcorn buckets, in a caucus the security of the count is not provided by the ballot container alone, but by the many eyes on the process, from people representing the different candidates — a layered security model that also applies to the general election.

The stark difference between the level of rumoring in past elections compared to the level of rumoring in the recent caucus raises the question of why this election was so quiet. As we have noted in previous work, errors, delays, and anomalies are most often utilized as evidence by those seeking to — rightly or wrongly — delegitimize election results. One theory, consistent with past research on rumors, is when online audiences and candidates have expectations confirmed, such errors might become uninteresting to them, as such results create for them little ambiguity or uncertainty that needs to be resolved by alternative explanations. The importance of these factors has been noted in our previous work on elections. Therefore, in the 2024 Iowa Republican Caucus, it might be the case that everyone involved in the process, including the candidates and online audiences, got what they expected and did not need to turn to any election errors or procedural issues to explain what was felt as a predictable result. In this view, supporters of DeSantis and Haley did not spread any rumors to explain their defeat as they did not expect to come in first, and therefore did not feel the need to explain an unexpected result as the product of fraud.

A second hypothesis, popular in conspiracy theory research, is that election rumors are for losers. Reviewing primary and caucus rumors of the past decade, our team found that Ron Paul, Bernie Sanders, Donald Trump, and their supporters were responsible for spreading a large percentage of online election rumors — particularly in primary contests that did not go their way. However, Trump’s overwhelming victory in the 2024 Iowa Caucus seems to have discouraged his supporters from searching for election rumors and explanations that would detract from the narrative of his decisive win.

Still, not every candidate who lost elections initiated such rumors. A third theory suggests the combination of a perceived loss or setback fuels such rumors primarily when an anti-establishment candidate loses and is willing to promote such rumors as part of an anti-establishment message. Ron Paul (2008, 2012), Bernie Sanders (2016, 2020) and Donald Trump (2016) were all anti-establishment candidates who went into the early primaries as underdogs, and used such allegations to promote a general anti-establishment message. In this view, Trump supporters have little incentive to undermine the narrative of their win, and the less populist views of Haley and DeSantis followers may not provide fertile ground for the spread of rumor, despite their loss.

Whatever theory ends up explaining behavior around the contests to come, the lack of election rumor — despite ample material to work with — remains one of the most striking elements of this past caucus. As candidates gear up for a race in New Hampshire that is likely to be closer, we will be looking to see if more ambiguous results — and a closer margin for Trump — produce a larger volume of election integrity allegations.

- Mike Caulfield is a CIP research scientist; Mert Can Bayar is a CIP postdoctoral scholar; and Ashlyn B. Aske is a CIP graduate research assistant.

- Photo at top: Former president Donald Trump speaks at an event in Las Vegas. (Photo by Gage Skidmore / Flickr via CC BY-SA 2.0 DEED)