2024 U.S. ELECTIONS RAPID RESEARCH BLOG

As voters head into the first-in-the-nation presidential caucus, recent allegations shared on X point to a “conflict of interest” in vote counting but no specific wrongdoing is described.

By Mike Caulfield

University of Washington

Center for an Informed Public

This is the first in a series of rapid research blog posts and rapid research analysis about the 2024 U.S. elections from the University of Washington’s Center for an Informed Public.

We now have seen one of the first electoral integrity conspiracy theories of the 2024 primary cycle. A number of accounts on X, formerly known as Twitter, are promoting a claim by conservative political activist Laura Loomer that a consultant allegedly hired by the Iowa Republican Party to assist with the vote-counting process has ties to Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis.

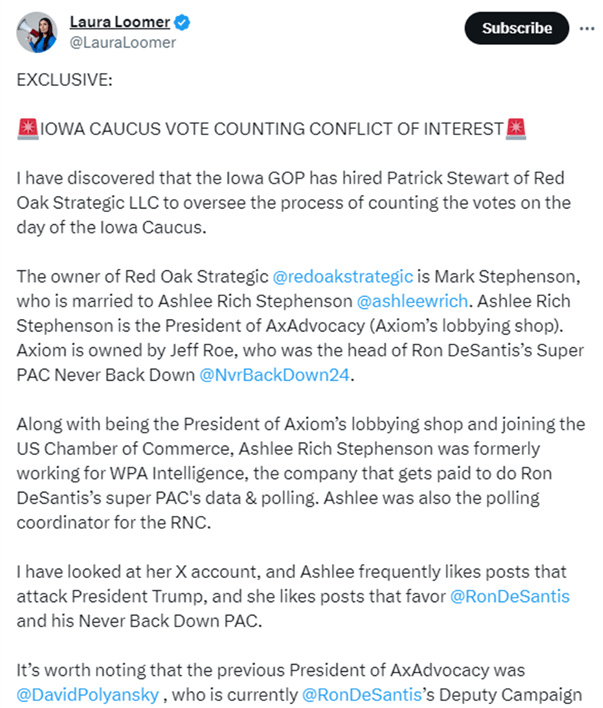

The beginning of Loomer’s January 12 post on X.

Some of the claims are sourced, and some not, but the initial post alleges under a framing headline using the term “conflict of interest”:

- A person named Patrick Stewart was hired to “oversee the process of counting the votes,” and Stewart works for Red Oak Strategic.

- Presumably Stewart was hired for data services around counting, though Loomer’s post does not provide more information.

- Red Oak Strategic is owned by Mark Stephenson.

- Mark Stephenson is married to Ashlee Rich Stephenson.

- Ashlee Rich Stephenson is the president of AxAdvocacy, which is the lobbying shop of Axiom.

- Axiom is owned by Jeff Roe, who was head of a DeSantis SuperPAC.

The post goes on to make other assertions about Ashlee Rich Stephenson’s work history and public opinions. Later posts by Loomer and others on X and elsewhere build on the rumor, asserting other connections of political figures to the company. A blog post by Loomer implies, for instance, that consulting fees paid by Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell might give him an early look at caucus results. Another Twitter post notes that Red Oak is an Amazon Web Services partner, and after January 6, 2021, Amazon had deplatformed a number of services said to have housed violent content — supposed evidence of another biased participant.

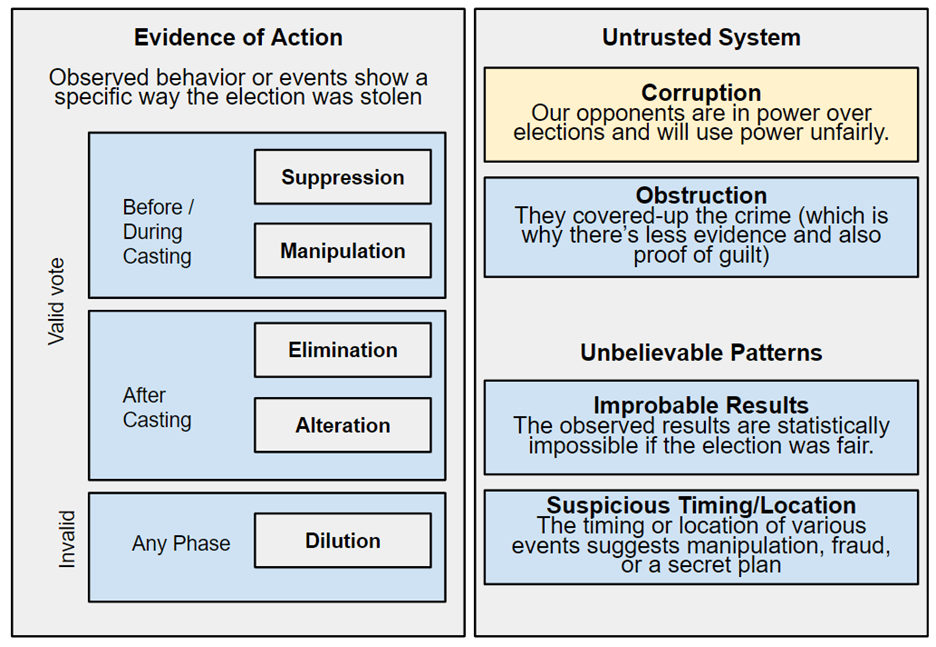

A familiar flurry of weak connections — in a densely connected field

Whether these connections are correctly described by Loomer and others we leave to others to pursue. As is often the case, the real question with election rumor is not whether the offered evidence is “real,” but whether when the full facts are known it can be said to support the claim for which it is advanced. Here the larger claim is one we label an “untrusted system” claim, with a subtype of corruption: no specific wrong-doing is described, but the system is said to be under the control of people who have at best conflicts of interest, at worst a history of election interference.

Such claims are common in election rumors. In fact, there was a similar set of claims at the last Iowa caucus, in the Democratic caucus. In 2020, a piece of software from the unfortunately named “Shadow Inc” was seen to be at the center of a delay in reporting Democratic Caucus results.

In that case the app was alternately linked by supporters of Bernie Sanders to Hillary Clinton’s former campaign manager Robby Mook and to Pete Buttigieg, in both cases using a variation of this game of “connections.”

Corruption claims can have validity, but ones that have to hop through a series of relationships or suggest relatively ordinary relationships are proof of corruption are generally weak. Such claims often make use of the fact that certain professional communities (whether political consultants, researchers, or cloud service providers) are surprisingly small and densely networked in ways outsiders might not appreciate. For instance, it might be odd if a randomly selected American happened to have a connection to the head of a DeSantis fundraising organization. But it is not odd at all that people in political consulting or political lobbying know people in political campaigns, or that high-profile political consulting organizations have a variety of high-profile political clients. It’s even less surprising when numerous “jumps” still must be made to connect them.

Corruption claims as ‘table-setting’ for more specific claims

Possibly because the caucus has not happened yet, the Red Oak Strategic allegations don’t propose any specific way in which the integrity of the election would be subverted through Red Oak Strategic’s participation in the process. In fact, it’s not even clear in the Twitter discourse what Red Oak Strategic’s role in the caucus is (the post does not even make clear whether Patrick Stewart is acting on behalf of the company or just employed by them).

Over time, corruption claims are usually paired with more specific claims about how a given entity might have undermined election integrity. Sometimes these are grounded in strong evidence. Many times they are pure speculation. A popular tweet about Shadow Inc. in 2020 implied a conspiracy theory that will be familiar to those who know spurious right-wing allegations of later that year: supposedly, just as Sanders was about to win his opponents had to find a way to “stop the count,” so the software — which depending on who you followed was said to be under either the influence of Clinton or Buttigieg partisans — had to go down. Or so the story went. Here’s example language from a tweet in 2020:

First, Pete Buttigieg stops Iowa polls from being published.

Then, with 111 votes for Bernie and 47 for Pete, they both receive 2 delegates at a caucus.

Now, he funded the app that was supposed to track the caucus but ended up crashing, delaying the results.

Right now, the Red Oak Strategic narrative isn’t tied to any specific event that has happened yet — but seems to be being prepped in case the margins for Trump are smaller than expected. A specific claim of “improbable results” or “suspicious timing” can be added later, or specific allegations on dilution or alteration of votes.

We leave it to the fact-checkers to look into the details of these claims, should they merit it. For now the surfacing of this claim seems to be confirmation of something that we have mentioned before — in the primary season we should be looking at precedents from both parties, and in fact some of the Sanders-era parallels may be particularly apt.

A Note on Terminology: Following a common practice in academic scholarship, we refer to the different elements of X (tweets, retweets, likes, follows) by the terms used in the community itself. Likewise, we use terms like “news twitter” and “crisis twitter,” both lower case, as the common names used on X to refer to these communities or discourse subgroups. When referring to the platform itself or associated policies, we use the term “X,” the legal name of the platform.

- Mike Caulfield is a research scientist at the University of Washington’s Center for an Informed Public.

- Photo at top: Republican presidential candidate Vivek Ramaswamy speaks in the rotunda of the Iowa State Capitol in Des Moines. (Photo by Gage Skidmore / Flickr via CC BY-SA 2.0 DEED)

- For additional updates from the Center for an Informed Public’s rapid research from the 2024 U.S. election cycle, follow Mike Caulfield on Bluesky, the CIP on Mastodon and LinkedIn and/or sign up to receive updates via email.