The solution to pervasive misinformation is not better facts, but better frames.

By Kate Starbird

University of Washington

Center for an Informed Public

Author’s note: This article emerges from insights garnered over almost a decade of collaborative research studying collective sensemaking online during crises and breaking news events, as well as conversations with external colleagues. In particular, I’d like to give credit to Dharma Dailey, Emma Spiro, Leo Stewart, and Tom Wilson for their early contributions to the framework presented here; to Zarine Kharazian, Stephen Prochaska, Adiza Awwal, and Julie Vera for recent research conversations that have re-ignited this work; to Mike Caulfield for insights about why this perspective is important for our current moment; and to Ira Hyman and Mert Can Bayar for their feedback on a first draft of this article.

Americans tend to agree that online misinformation is a critical problem. However, there is less agreement about what exactly that problem consists of — or how we should address it. In this essay, I describe a framework for examining online rumors, conspiracy theories, and disinformation through the lens of collective sensemaking. This perspective could inform more nuanced understandings, new ways to operationalize and study these phenomena, and alternative approaches for addressing them.

Our research team at UW has been studying misinformation for more than a decade, examining online rumors during crisis events, disinformation campaigns in geopolitical conflict, and conspiracy theories about elections. In our internal conversations, we have repeatedly noted a misalignment between how the general public — and even much of the research — talks about misinformation and what we see in our analyses of how falsehoods take root and spread online.

We repeatedly see the problem of misinformation described as an issue of bad “facts.” This line of thinking suggests that if we just had better and more accurate facts, we would all be better informed and our understandings more aligned with some kind of objective truth. However, our research suggests the problem is not merely about bad facts. Though fabrications and outright lies certainly contribute to the challenge of misinformation, we are more often misled not by false evidence but by misinterpretations and mischaracterizations — dynamics of a collective sensemaking process gone awry.

The SharpieGate case: Rumors, conspiracy theories, and disinformation and the 2020 election

Let me provide an example. After the 2020 U.S. election, false claims about voting sowed doubt in the election results and played a role in motivating the January 6, 2021, attack on the U.S. Capitol. Our team studied how hundreds of these claims — or rumors — took shape and spread across social media platforms and out through the broader information ecosystem. One of the cases we studied most closely was SharpieGate.

SharpieGate began on Election Day (November 3, 2020) with social media posts from voters noting that the Sharpie pens provided at polling locations were bleeding through their ballots. Initially, the tone of these posts was one of concern, reflecting worries that their votes might not count. Election officials, including those in Maricopa County, Arizona — a massive county in a swing state — attempted to alleviate concerns, explaining that the ballots were designed to be completed with Sharpie pens, and that bleed-through would not affect vote-counting. Unfortunately, these explanations failed to slow the spread of rumors.

As time went on, people began to interpret the bleed-through with suspicion, wondering if the pens were part of an intentional effort to disenfranchise specifically Republican voters, who were known to vote in higher proportions on election day. Shortly after the state of Arizona was called by Fox News for candidate Biden, rumors about Sharpie pens went viral as false conspiracy theories that the pens were part of a “voter fraud” scheme against then-President Trump.

In published research, we describe the evolution and spread of SharpieGate as part of a “participatory disinformation” campaign. We highlight how, prior to the election, elites in politics and media — including President Trump himself — set an expectation (or a frame) of a “rigged election.” As the election progressed, many of President Trump’s supporters went to the polls (or their mailboxes) and misinterpreted their own experiences through that lens. Later, they went online, sharing those experiences and seeing other “evidence” from around the country, which they interpreted through the same “rigged election” or “voter fraud” frame.

SharpieGate was just one of many examples of this phenomenon, which included similar stories about discarded mail-in ballots, system glitches, statistical anomalies, vote transporting equipment, vote-counting procedures, and more. The Big Lie took shape not merely as a series of lies communicated from elites to their audiences, but also as a series of misinterpretations and mischaracterizations from a motivated crowd who was willing (and in some cases eager) to misperceive the world through the “rigged election” frame. Online influencers played an important role as well, gathering that evidence, echoing it back down to their audiences to motivate more contributions, and filtering it up to elites who would use it to reinforce their “rigged election” frames.

Over and over again, when we opened the hood of myriad “voter fraud” rumors about everything from voting machine “glitches” to “vote dumps,” it wasn’t that people were being misled by the bad evidence — they were being misled by faulty frames.

Intellectual roots of collective sensemaking

The idea of collective sensemaking can help us understand, conceptualize, and communicate about online misinformation — in particular around the dynamics of rumors, conspiracy theories, and what we call “participatory disinformation.”

Our (my colleagues and my) understandings of collective sensemaking stem from two theoretical traditions. The first draws from research within formal organizations, especially as they understand and respond to crisis events. Working in that context Karl Weick explained that, “The basic idea of sensemaking is that reality is an ongoing accomplishment that emerges from efforts to create order and make retrospective sense of what occurs.” In other words, our understanding of the world around us and events that occur within that world takes shape through both individual and social processes — i.e., sensemaking — through which we interpret our experiences.

The second tradition we draw upon is the study of rumor and rumoring, a field of study with a long history. Rumors are a common feature of crisis events, where they emerge from a collective effort to make sense of uncertain and ambiguous information under conditions of anxiety. Collective sensemaking, in this tradition, takes the form of “improvised news” sharing within informal groups. From this perspective, rumors are natural byproducts of the emergent social and psychological process that occurs as people come together to collectively process novel events.

Sensemaking as an interactive process between evidence, interpretations, and frames

Fusing those traditions and opening up the concept further, collective sensemaking can be understood as an interactive process between evidence, interpretations, and frames.

Frames, according to esteemed sociologist Erving Goffman, are mental schema that we use to interpret and give meaning to experiences. In Goffman’s perspective, what we know as reality isn’t some objective truth. Instead, we come to know the world through interpretations of the evidence we encounter, where each interpretation is shaped by existing cognitive structures that guide us in assigning meaning to evidence and for intuiting how different pieces of evidence fit together.

Building off both Goffman and Weick, Klein and colleagues present a “data-frame” theory of sensemaking that describes it as a two-way, interactive process where our existing frames help us select and interpret data (or evidence), and those data help us update, evolve, and (when needed) swap out our frames. When making sense of the world around us, we cannot take into account all available information. We have to focus, to decide what to pull into the foreground and what to let fade into the background. We have to select some pieces, ideally the ones that are most relevant to the situation or problem at hand. And we have to leave some pieces of evidence outside of our consideration. This process of selecting evidence is guided by our current frame or our available frames — i.e., which have, in turn, been shaped by our experiences making sense of similar situations that we have encountered before.

So, our frames shape what evidence we choose to include in our sensemaking. But the available evidence also guides our selection of the appropriate frame — or at least it should guide our frame selection. In an open or healthy sensemaking process, the availability of evidence constrains the available frames, and we work to find the best frame for interpreting the evidence at hand. Each of us may have a different set of available frames due to our past experiences — including our upbringing, education, professional training, and life experiences. (Frames are also actively shaped by our media environments, an idea I’ll come back to shortly).

In trying to operationalize this theory to study social media data, my colleagues and I found it productive to add a third component, interpretations. When making sense of a situation, after selecting a frame to work with from our available set of frames, we attempt to fit the evidence we have into that frame — which guides how we interpret that evidence.

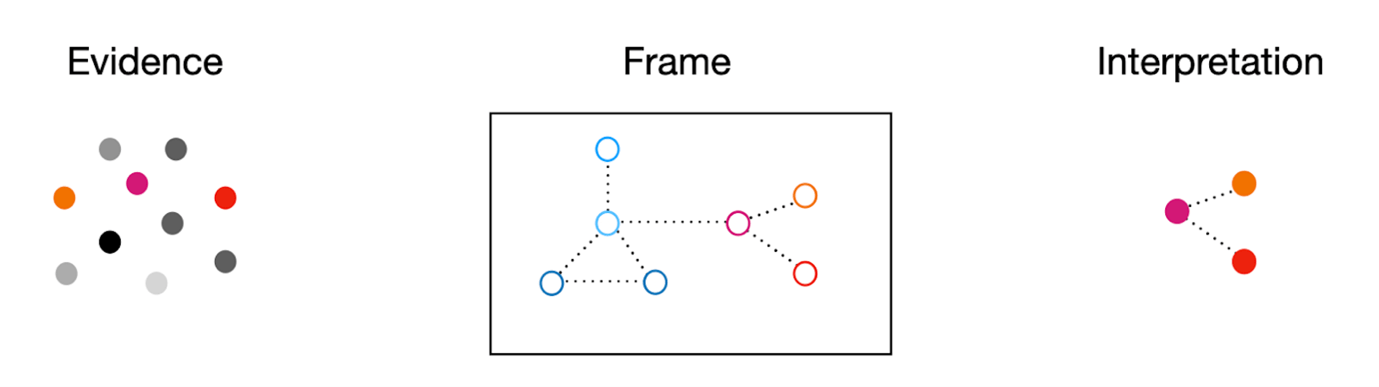

The figures below are a very simple illustration of evidence, a frame, and an interpretation. The frame provides structure for selecting evidence that will result in certain interpretations, both of the meaning of specific pieces of evidence and for the relationships between two or more pieces of evidence.

Available evidence shapes what frames are available to us, and our available frames shape what evidence we choose to include in our sensemaking, how we interpret the meaning of individual pieces of evidence, and how we connect different pieces of evidence.

Available evidence shapes what frames are available to us, and our available frames shape what evidence we choose to include in our sensemaking, how we interpret the meaning of individual pieces of evidence, and how we connect different pieces of evidence.

When the evidence does not quite fit our selected frame, we can go find new evidence, or we can swap out the current frame for another one, adjust the current frame to better fit the evidence, or construct a new frame. The sensemaking process takes shape through this interactive process of fitting evidence to frames and frames to evidence, with a primary outcome being interpretations.

Another less direct outcome is an updated frame repertoire, the set of frames we can choose from. A sensemaking process can produce a new frame or strengthen an existing frame, making it more readily available for future use. Meanwhile, frames that go unused may grow weaker and less salient over time.

Klein and colleagues theorize that the nature of expertise lies in having more and higher quality frames to draw from. Selecting an appropriate frame is important for quickly and productively assessing a novel situation. Yet, each person has a unique repertoire of frames from which to draw. Let me provide an example (with another example embedded within it) — of reports of unidentified flying objects or UFOs.

A family-friendly framing exercise

In recent months, there has been renewed attention to reports of UFOs in the United States. These reports go back decades. Many of the most compelling reports consist of a first-person sighting — in some cases by military pilots and other respected individuals — of something in the sky that appeared to be an aircraft but moved in a way that the observer determined to be beyond the capacity of current human-made technology. At one level, we can examine the first-person experiences described within these reports through a sensemaking lens, whereby the observer attempted first to fit the evidence (e.g., the trajectory of light in the night sky) into an existing frame (e.g., knowledge of how terrestrial aircraft move), and then, after failing to find a fit, chose an extra-terrestrial frame as a better fit for interpreting the available evidence.

On another level, we can look at how everyday people are making sense of these collections of reports, an exercise I recently participated in with family members.

One family member views this collection of UFO reports as likely evidence of aliens visiting Earth. This family member is a fan of conspiracy theories, a little superstitious, and appreciates a little magic in the world. She chose a frame that reflects the flavor of her broader repertoire. Another family member, a former military officer with knowledge of military discipline and discretion, selected a frame that interpreted the reports as evidence not of UFOs, but of secret military programs that involved testing equipment that most people did not know existed. (In other words, he thought the observers were misperceiving these terrestrial aircraft as extraterrestrial aircraft.) And finally I, the conspiracy skeptic, chose a very boring frame and argued that most of these reports were likely just people misinterpreting existing (known) aircraft, meteors, radar noise, and other natural phenomena through a “UFO” frame.

Each of us chose to ignore some evidence (that which did not fit our frames) and highlight other evidence as we assembled it into our frames and produced our arguments. The proponent of the aliens explanation discarded evidence around the dearth of similar reports of UFOs prior to the dawn of human-made aircraft (which would suggest they are more related to human flight than alien visitation). I chose not to give much weight to the expertise and detailed testimony of some of the more credible observers. To be honest, the former military officer seemed to be accounting for a more complete set of evidence, so I might have to give him the win on this one. In any case, it was a fun and less politically charged exercise than others, so I recommend it for those who want to play along at home!

Framing as the social (and often strategic) shaping of frames

For the past few sections, I have focused on sensemaking as an individual process. But collective sensemaking is a social process. The frames we use are not ours alone. They are shaped through our experiences, including our social experiences, through negotiation with others, and through our interaction with media and other discourse. Additionally, our group identity — i.e., our self-perceived membership in social or political groups — will often influence the frames we select (and consequently, the evidence we focus upon). When the former military officer in the above example was interpreting reports of UFOs as a secret military program, he was applying a frame that was initially constructed through his professional experiences (i.e., learning how the military works) and later reinforced by television documentaries featuring other former officers offering similar interpretations of UFOs.

Scholars who study collective action explain how frames are socially and in some cases strategically constructed (and promoted, adapted, countered, etc.) through social processes — i.e., framing — that shape how social groups collectively interpret their experiences and understand the world. If one accepts Weick’s view of reality as an ongoing accomplishment and Goffman’s explanation of frames providing the structure for interpreting experiences, it follows that if someone (or a group of someones) can shape the frames people use, then they can shape reality. It’s a powerful idea. And one that informs the strategy of many political communicators.

Collective sensemaking — and where it can go awry

Fusing these concepts and perspectives together, we can understand collective sensemaking as a social process of meaning-making that takes shape through interactions around evidence, interpretations, frames — and includes framing activities.

Our team is working to operationalize this framework to study how rumors, a byproduct of the collective sensemaking process, take shape and spread online. We are exploring how, within the collective sensemaking process, people share and offer interpretations of evidence, introduce frames both explicitly and implicitly, challenge frames being used by others, advocate for frames they prefer, and draw attention to specific pieces of evidence that counter some frames and support others. This work is ongoing, but I want to provide a few early insights about how this framework may help us understand how collective sensemaking can go awry.

In an ideal sensemaking process, people faced with novel information are able to rapidly absorb, order, interpret, and act upon that information in productive ways. Surveying the available evidence, a person or group will first select a frame from their repertoire to help them interpret what they’re experiencing. This frame helps them interpret the meaning of individual pieces of evidence and infer relationships between multiple pieces of evidence. If the initial frame is inadequate — e.g., if interpretations from the given frame are inconsistent with existing evidence, or new pieces of evidence cannot be accounted for by the current frame — then the sensemaker can adapt the current frame, switch it out for a new one, or begin to construct a new frame from scratch.

Working in the context of crisis response, Weick explained that one factor in maladaptive sensemaking is when decision-makers anchor too quickly on the wrong frame. An initial bad frame can lead sensemakers to misinterpret a situation, and perhaps more problematically, to overlook or exclude key evidence — evidence that may remain out of view even after they recognize the need to adjust or replace their frame. Frame selection, and especially the selection of the first frame, is therefore one place where sensemaking processes can go awry.

Frame selection at the individual level likely involves multiple cognitive processes. Without going too deeply into those, I’m going to hypothesize that, just like we all have our own repertoire of frames, we also have frames that are more salient than others. In other words, each of us has preferred frames (for reasons that include prior experience, individual and group identity, media exposure, and more) that are easier for us to call up. Additionally, we are often motivated to select specific frames that enable us to interpret evidence in ways that align with preferred outcomes — e.g., during sports games, we prefer to see the outcome of a controversial play in a way that privileges our own team.

Putting these different ideas into conversation with each other leads to significant insights about rumors, conspiracy theorizing, and disinformation:

- Insight #1: Rumoring is collective sensemaking. Rumors are a natural byproduct of the sensemaking process. We often conflate the term rumor with false rumor, but rumors can turn out to be true, and even false rumors can contain elements of truth. Rumors, even false rumors, contain valuable information for public communicators — both about the “facts” on the ground of a situation as well as the frames that people are using to interpret those facts. And, for cases of harmful false rumors, rumor correction is not just about getting people the right facts. It also requires helping people access frames that will result in more accurate interpretations.

- Insight #2: Conspiracy theorizing is a patterned and constrained form of sensemaking where individuals and groups repeatedly anchor on a small number of “conspiracy” frames — one where government and media cannot be trusted, where things are not what they seem, and where events are put into motion by secret cabals of powerful actors. When a new situation occurs, conspiracy theorists tend to select one of these frames (rather than another frame from their broader repertoire) and then they work to assemble the evidence to fit that conspiracy frame. As they do so, they often either fail to account for evidence that counters their frame or they rely upon interpretations of that evidence, previously embedded in the structure of the frame, that twist it into “part of the conspiracy.”

- Insight #3: Disinformation is a manipulated form of sensemaking where motivated actors intentionally work to shape the outcomes of the sensemaking process to support their goals and objectives. In his book on Soviet-style active measures, Thomas Rid describes how disinformation purveyors view the “social construction of reality” not as a descriptive theory, but as a strategy, with the idea that to shape discourse is to shape how others perceive reality. Disinformation can work by introducing false evidence, such as a forgery or a hoax event. But it can also work by shaping the frames through which people interpret the evidence they see — e.g., by encouraging people to interpret benign glitches with voting (or just parts of the voting process that they don’t fully understand) as systematic voter fraud.

Returning to SharpieGate

The SharpieGate case illustrates both of these dynamics. Prior to the 2020 election, elites in conservative politics and media created and repeatedly promoted the frame of a “rigged election.” President Trump himself made hundreds of statements alleging systematic voter fraud and warning the election would be stolen from him — and that his voters would be cheated. This rhetoric shaped how Trump’s supporters interpreted their own voting experiences, as well as the experiences shared by others, on and after election day.

For many Republican voters in Arizona, the “rigged election” frame was front of mind as they went to the polls. Anchoring on it led them to misinterpret the ink bleeding through their ballots as potentially part of an effort to disenfranchise them. They focused on certain details — like the fact that Sharpie pens had been provided by election officials and that Republicans were more likely to vote in person on election day — that supported this misinterpretation. And they excluded, rejected, or just failed to discover counter-evidence that the ballots were designed to be used with Sharpie pens and the bleed-through would not affect the vote-counting. In many cases, these misinterpretations were sincere and resulted in real concern by real voters that they had been disenfranchised.

They also became opportunities for politically motivated actors to promote and reinforce the rigged election frame. Online influencers and political pundits repeated and amplified the misinterpretations, while ignoring corrections provided by local election officials. This strengthened the salience of the “rigged election” frame among their audiences, who would go on to use that frame to (mis)interpret other events and evidence in a similar way.

From this perspective, the effort to sow doubt in voting processes and election results was a participatory disinformation campaign, a collaboration between political elites, online influencers, and their audiences that worked first by creating a faulty frame, and then by gathering “evidence” that could be accidentally misinterpreted or intentionally mischaracterized to support that frame.

A vast majority of false claims about the 2020 election — from misinterpretations of ballot envelopes in dumpsters, voting glitches, statistical anomalies, videos of election officials counting votes, vehicles used for transporting votes, etc. — follow these same dynamics. They were very rarely about false evidence. They almost always relied on false impressions or intentional mischaracterizations.

Once the frame of a rigged election became salient among a large proportion of Republican voters and Trump-supporters, they did not need to be told that they would be cheated or had been cheated. Instead, the frame led them to consistently misinterpret their own voting experiences as well as other events of the day as part of the broader “conspiracy” to disenfranchise them.

Reframing the problem of misinformation

In writing this article, I aimed to advocate for revising — or, if I may, reframing — our understanding of online misinformation. Approaching misinformation (and related concepts of rumoring, conspiracy theorizing, and disinformation) through the lens of collective sensemaking could be productive for researchers, for journalists and other public communicators, and for everyday people.

For researchers, I believe the collective sensemaking framework I present here opens up opportunities for both a more nuanced understanding of online misinformation and a way to operationalize its production and spread across the three dimensions of evidence, frames, and (mis)interpretations.

For individuals grappling with confusing and often contentious information spaces, I propose that revealing the role frames play within our sensemaking processes may help us understand why others have completely different explanations for the same sets of evidence — and why we sometimes feel we are living in different realities. One pathway to greater empathy may be through (temporarily) swapping out our frame for one of the frames used by someone on the other “side” of a conversation, to better understand where they are coming from. That doesn’t mean we have to agree with them, but it may help us more precisely identify why our perspectives are so different — and could provide a pathway for mutual understanding.

For journalists and public communicators (e.g., public health communicators and election officials), I hope this lens of collective sensemaking provides insight into the disconnect between the processes that underlie the spread of falsehoods, especially those that emerge from misinterpretations and mischaracterizations as opposed to outright lies, and the simplistic ways we sometimes talk about and attempt to counter misinformation. Getting people to revise their views around distinct claims may not be effective. The communicative solution to pervasive misinformation is not better facts, but better frames. Calling back to the example of SharpieGate, instead of focusing on “rumor control,” it may be valuable for election officials (and journalists) to proactively communicate a frame of election integrity which highlights the many layers of election security and explains that while mistakes happen, they are rarely intentional, do not consistently benefit one party, and are almost always easily rectified by another protective layer in the process.

The framework I present here, focused on the cognitive aspects of collective sensemaking isn’t complete. It will need expansion to account for other factors that shape the sensemaking process, including motivations, emotions, and identities. But I hope that it will be a productive starting point for advancing our understandings of — and informing more effective strategic to mitigate — online misinformation.

***

Kate Starbird is director and co-founder of the Center for an Informed Public at the University of Washington, where she’s an associate professor in the Department of Human Centered Design & Engineering.

PHOTO AT TOP: Construction workers install a frame in a wall of a house in Greendale, Wisconsin in 1937 (Lee Russell / U.S. Farm Security Administration via Office of War Information Photograph Collection / Library of Congress)