By Kate Starbird

Associate Professor, University of Washington Human Centered Design & Engineering

Director and Co-Founder, UW Center for an Informed Public

As a researcher of rumors and disinformation, it is especially frustrating to become a target of attempts to distort the truth for political gain. I know how difficult it can be to mitigate the effects of reputational smears, and I am acutely aware of the risk that trying to refute false claims can give them more attention and thereby increase the damage they inflict. But I also recognize the importance of correcting false claims and calling out manipulative tactics, especially when those claims include attempts to permanently shift the historical record and those tactics are employed by powerful political actors against vulnerable targets.

On June 26, 2023, Republicans on the U.S. House of Representatives Committee on the Judiciary and the Select Subcommittee on the Weaponization of the Federal Government (The Committee) released a document titled, “The Weaponization of CISA: How a ‘Cybersecurity’ Agency Colluded with Big Tech and ‘Disinformation’ Partners to Censor Americans.” This document contains many inaccuracies and creates false impressions about me, my research, and my participation on an external advisory committee for the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) — even after I sat with The Committee for a 4.5-hour interview. Specifically, The Committee’s interim report mischaracterizes the work of a voluntary advisory committee, conflates timelines, and selectively presents and recontextualizes content from emails and meeting notes provided to The Committee to weave a false narrative.

Here, I provide key context that is missing from The Committee’s interim report, explain some of the tactics it used to create false impressions, and provide factual information to correct them. Rather than addressing all of the report’s many falsehoods and inaccuracies, which would demand responding to nearly all of the document’s 37 pages, I’ll focus on particularly egregious mischaracterizations that directly reference me and my work with an external advisory committee for CISA.

***

Context

- CISA is an agency within the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS). It was established in 2018 through the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency Act, passed by Congress in recognition that our critical infrastructure was vulnerable to cyber and other threats, and signed into law by then-President Trump. In 2020, CISA participated in efforts to address election mis- and disinformation, including establishing a “rumor control” website to address false rumors about election processes. This work included coordinating information sharing between local and state election officials and social media platforms, which play an outsized role in mediating the spread of rumors. These efforts, which took place in 2020 under then-CISA Director Chris Krebs, an appointee of President Trump, have become the focus of both legitimate criticism (invoking discussions about what the guardrails for collaboration between government and social media platforms should be) and motivated conspiracy theorizing (falsely alleging, among other things, a massive and secret conspiracy to censor conservative voices as opposed to a nonpartisan effort to mitigate false claims about election procedures, vote-counting processes, and results).

- During the 2020 election cycle, my team (at the University of Washington) and I did not have any direct contact with any CISA employees. And I personally did not become a volunteer member of the CISA advisory committee until later, in 2021.

- In June 2021, under the Biden Administration but with direction from the U.S. Congress, CISA formed the Cybersecurity Advisory Committee (CSAC) to provide “strategic and actionable recommendations to the CISA Director on a range of cybersecurity issues, topics, and challenges.” The CSAC is an external advisory board where members volunteer their time and expertise to, very specifically, provide recommendations to the director for her consideration. This service is publicly recognized. Members’ names are posted to a public website and there are opportunities for members of the public, including journalists, to attend and participate in open sessions during quarterly meetings.

- In Autumn 2021, CISA Director Jen Easterly, who had worked previously under both the Obama and W. Bush administrations, invited me to join the CSAC. Later, she would ask me to chair the newly established “Protecting Critical Infrastructure from Misinformation & Disinformation” (MDM) Subcommittee. The MDM Subcommittee was one of several within the CSAC. (MDM is an acronym that the government uses to mean Misinformation, Disinformation, and Malinformation.)

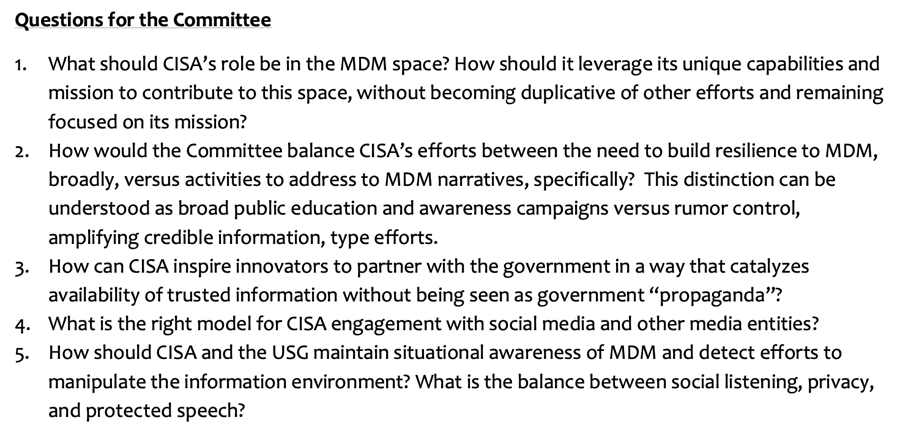

- I accepted Director Easterly’s invitation to serve in a voluntary capacity on the CSAC and MDM Subcommittee primarily to help ensure the integrity of our federal and state elections. Director Easterly seeded our discussions with a list of questions (shown below) and an “ask” that we generate a short report focused around recommendations for how CISA should approach the challenges of mis- and disinformation in the context of critical infrastructure.

- Early in the process, we chose to focus on election-related work, in large part due to the acute need as we were approaching the midterms. In crafting our recommendations, the MDM Subcommittee met remotely every other week for approximately one hour, over the course of approximately seven months. During these meetings, the MDM Subcommittee worked to understand CISA’s mission, its current work, and the needs of local and state election officials — and to translate that knowledge into a set of written recommendations. In about a third of the meetings, external speakers were invited to provide insights into specific aspects of CISA’s work and the challenges faced by election officials. In addition to these meetings (which were recorded in contemporaneous meeting notes), MDM Subcommittee members also attended quarterly meetings with the broader advisory committee to update them on their work. We produced two sets of recommendations that addressed some, but not all of the questions initially given to us by Director Easterly. Both sets of recommendations were publicly presented during meetings, one in June 2022 and the other in September 2022.

- Email communications and meeting notes from our MDM Subcommittee’s deliberations are now part of the public record. Significantly, the notes from these meetings are not exact transcripts, but rough meeting notes taken by a CISA employee who was not a context expert. They do not always accurately reflect the exact language or nuance of those conversations.

***

The Committee’s interim report repeatedly mischaracterized the work of the CSAC and MDM Subcommittee to push a false and misleading narrative. These are just some of the most glaring issues:

1. The MDM Subcommittee that I chaired did not participate in or recommend CISA take part in any censorship efforts.

The report’s headline asserts that CISA “colluded with big tech partners to censor Americans.” I believe that narrative to be profoundly misleading, but I will let CISA defend itself. I will, however, point out where it’s specifically misleading about my colleagues and me on the MDM Subcommittee. Strangely, the majority of the interim report focuses not on the activities of CISA, but on the work of our external advisory MDM Subcommittee. The headline, in combination with the extensive focus of the report on our work, creates a false impression that the MDM Subcommittee participated in “censorship” activities through our work with CISA.

This impression is wrong across numerous dimensions. The MDM Subcommittee served CISA exclusively in an advisory — not an operational — capacity. The MDM Subcommittee’s sole task was to produce recommendations to Director Easterly for her review and to accept or reject as she saw fit. The MDM Subcommittee was not actively involved in any CISA operations. Quite specifically, the MDM Subcommittee did not alert platforms to content or recommend that social media platforms take any action, either related to a specific piece of content or around policies more generally.

Furthermore, the MDM Subcommittee did not orchestrate, participate in, or even recommend that CISA take part in activities that could be construed as “censorship”, even in the strategically loose conceptualization pushed within The Committee’s interim report. On the contrary, in our recommendations to Director Easterly, the MDM Subcommittee articulated a vision of CISA’s work focused on supporting local and state election officials, building resilience generally to mis- and disinformation through education, and proactively addressing specific cases of mis- and disinformation through communication, not censorship.

2. This mischaracterization of our deliberations and recommendations as revolving around “censorship” anchors an entirely false narrative and echoes throughout the report, providing a false context that enables further mischaracterizations of our communications.

Recent revelations — which occurred after the MDM Subcommittee had completed its work — indicate that, between 2018 and 2020, some CISA employees sent messages to social media platforms alerting them to content containing false information about election processes and procedures. The Committee’s interim report attempts to frame this “switchboarding” activity as “censorship,” and while I do not agree with that framing, I do agree there should be further discussion and the establishment of guidelines for government employees around communicating with social media platforms going forward.

However, in pursuing political objectives, The Committee obscures key contextual details — e.g., that this activity was focused on preventing people from being disenfranchised by misleading information about when and where to vote, and not indicative of broad “censorship of conservative voices,” an accusation implied by the report. Additionally, by omitting clarifying information about the timing and opacity of these activities, The Committee creates a false impression — which then echoes throughout the report — that these “switchboarding” activities were related to the MDM Subcommittee’s work.

The CISA activities that The Committee’s report refers to as “censorship” occurred prior to the convening of the CSAC and the MDM Subcommittee. According to CISA, its employees participated in “switchboarding” during the 2018 and 2020 elections (during the Trump administration). The MDM Subcommittee convened in December 2021. CISA has now explained that it was not partaking in “switchboarding” during the time that our MDM Subcommittee was meeting, and it has since officially discontinued those activities. The timeline reveals that “switchboarding” activities, which have become the focus of “censorship” claims, occurred prior to the convening of the MDM Subcommittee, did not happen while the MDM Subcommittee was meeting, and have not resumed after the MDM Subcommittee completed its work.

The MDM Subcommittee did not participate in “switchboarding”, did not have any substantive discussions about “switchboarding”, and did not make any recommendations about “switchboarding.” Separate from the MDM subcommittee’s work, CISA decided to not continue its “switchboarding” work in 2022. Subcommittee member Kim Wyman relayed that information to the MDM subcommittee on July 26, 2022. There was no follow-up discussion; that was the first and only time the term and topic came up in our meetings.

3. The MDM Subcommittee’s deliberations about “social listening” and “monitoring” were not related to censorship or “switchboarding.”

In her initial communications with the MDM Subcommittee, Director Easterly asked us to make recommendations about how to balance “social listening, privacy, and protected speech.” This question is relevant to work addressing election misinformation and disinformation, because to provide corrective information to false rumors about election processes and procedures, it is helpful to know what rumors are spreading.

Building off their false characterization of our work as focusing on censorship, The Committee’s interim report repeatedly insinuates, falsely, that our deliberations were about surveillance in service of censorship. But across all of our deliberations, including the content excerpted in the report about “monitoring” social media, we were not talking about monitoring in service of censorship or switchboarding, but about potentially using publicly available digital data, including content shared on public social media platforms and online websites, to gain situational awareness about election-related rumors. If committee members had asked me to clarify this during my interview, I would have pointed them to this 2010 paper, which I co-authored, the first to discuss using Twitter data for situational awareness during crisis events. The MDM Subcommittee was not deliberating about surveillance in service of censorship, but about how to help local and state election officials figure out what rumors were spreading about their election processes so that they could help their voters find accurate information.

4. The MDM Subcommittee chose not to make recommendations related to social media listening (or “monitoring”), not to hide our work, but because we determined those questions to be beyond the capacity of our small MDM Subcommittee and its limited timeline.

In the end, the MDM Subcommittee determined that making recommendations around social listening was beyond our capacity. There remain open questions and conflicting views about whether and how government entities can leverage public information shared by U.S. citizens on social media for situational awareness. We did not feel that our small MDM Subcommittee, in its limited time, could resolve these. In its interim report, The Committee falsely alleges that the MDM Subcommittee removed the term “monitoring” from our recommendations to hide “surveillance” by CISA. This is entirely false.

On the contrary, we decided to remove the term “monitoring” from our recommendations because we determined the issue to be above our volunteer pay grade — not to hide anything about our work or CISA’s activities.

5. The MDM Subcommittee did not advocate for circumventing government restrictions by outsourcing surveillance to third-party organizations.

The Committee’s interim report repeatedly mischaracterizes our deliberations around social listening to advance a false allegation that we were advocating for outsourcing surveillance in service of censorship to third parties. For example, The Committee’s interim report features a comment from Suzanne Spaulding, an MDM Subcommittee member, on a late draft of our recommendations where she writes, “Just as a note, CISA doesn’t monitor private networks. It relies on third parties to detect and notify it of malicious activity in non-government networks. Similarly, CISA may decide not to monitor media for MDM but, instead, to rely upon third parties to notify it of problems that could threaten critical functions.” The Committee’s interim report argues this exchange demonstrates that the MDM Subcommittee was still looking for ways to circumvent the First Amendment by having third parties monitor social media. This is not what was happening.

This exchange instead relates to how CISA gathers information about cybersecurity attacks (e.g. computer viruses and hacks) — i.e., primarily through private companies that detect these issues within their own or others’ infrastructure. Spaulding was suggesting that CISA take a similar approach to mis- and disinformation by passively receiving information from third parties, such as researchers, local election officials and the social media platforms themselves, about disinformation circulating on social media. This is what we end up advocating for in our June 2022 recommendations, writing, “CISA’s activities should be similar to the Agency’s actions to detect, warn about, and mitigate other threats to critical functions (e.g., cybersecurity threats).” There would be a significant difference between CISA relying on third parties to independently share disinformation with it, and CISA ordering third parties to monitor social media for certain types of disinformation.

6. The MDM Subcommittee was committed to transparency throughout the process.

The Committee’s interim report repeatedly pushes a false narrative of secrecy. This includes a line of false accusations that the MDM Subcommittee engaged in efforts to cover-up our work and the activities of CISA. In presenting “evidence” to support these false accusations, the report repeatedly mischaracterizes comments from draft documents and email exchanges between MDM Subcommittee member Suzanne Spaulding and myself. More troublingly, it ignores clarifying testimony that I provided to The Committee on June 6, 2023.

The MDM Subcommittee did not endeavor, in any way, to cover-up our work or the activities of CISA. Quite to the contrary, when we perceived that potential critics did not know that we were working to advise CISA on the challenges of MDM, we took additional steps to reach out to let people know we were there.

From the very beginning, the broader CSAC and MDM Subcommittee understood our committee and its work to be public. Committee members’ names were available on a CISA website devoted to the CSAC. Quarterly CSAC meetings included public sessions where subcommittee chairs reported on the work of their group. And we knew that our final recommendations would be public documents.

In late April 2022, as we were preparing our first set of recommendations, our MDM Subcommittee members first became aware of DHS’s “Disinformation Governance Board” (DGB), a group with which we had no connection. We also noted the growing criticism of that effort, which contained legitimate concerns about government overreach as well as politically motivated exaggerations and personal attacks. In the following weeks, we grew concerned that bad faith critics, more concerned with scoring political points than solving problems, would parlay attacks on the DGB into attacks on our unrelated MDM Subcommittee. We then realized that it was likely that most people were unaware of our MDM Subcommittee, and that we needed to take action to correct this. We worked to develop a strategy to proactively communicate about our work with potential critics. In its interim report, The Committee highlights my comment that our MDM Subcommittee needed to be “careful” in creating this strategy, suggesting that meant that we needed to hide or conceal our work from the public. That is not what I meant. When I said we needed to be “careful,” I meant we should anticipate how things we said could be taken out of context and mischaracterized — exactly like they are today.

The Committee’s interim report falsely portrays our communications around these concerns as trying to hide our MDM Subcommittee’s work. Among other misrepresentations, to push that “cover-up” narrative, The Committee’s report misleadingly presents a comment from a CISA employee (not a subcommittee member) informing our MDM Subcommittee that, per existing rules about communicating our work, we were not allowed to share our recommendations with people outside the CSAC advisory committee prior to submitting them to Director Easterly. This comment wasn’t about hiding, but about following existing committee rules. The Committee’s report then omits the fact that we adapted our plans, and Spaulding and I successfully spoke to two potential critics (one from either side of the political spectrum) about the work of the MDM Subcommittee, but without mentioning our specific recommendations.

Contrary to the interim report’s false accusations, our MDM Subcommittee members repeatedly worked towards transparency. After the DGB debacle, in recognition that our MDM Subcommittee was vulnerable to attacks like those we are experiencing now, we could have opted for secrecy and chosen not to release our recommendations. Instead we chose to continue, chose to proactively reach out to critics, and chose to submit two sets of recommendations for public scrutiny.

7. The MDM Subcommittee respected the First Amendment in all of its work.

The Committee’s interim report devotes more than a page of text to describing the protections of the First Amendment and goes on to falsely suggest that the MDM subcommittee sought to subvert the First Amendment. To create this false impression, the report cherry-picks emails and selectively portrays notes from our MDM Subcommittee’s deliberative process — often obscuring and in some cases intentionally distorting the original context.

A broader and objective look at the numerous records provided to The Committee shows that, contrary to the interim report’s false narrative, the MDM Subcommittee gave significant consideration to the First Amendment in all of our work, and explicitly did so in our recommendations to Director Easterly. In the first page of our June recommendations, we write that the recommendations were intended “to protect critical functions from the risks of MD, while being sensitive to and appreciating the government’s limited role with respect to the regulation or restriction of speech.” The Committee’s interim report knowingly disregards this fact, and creates a false impression while citing no recommendation or activity by the MDM Subcommittee that comes close to violating the First Amendment.