As Russia’s war in Ukraine continues into its seventh week, researchers at the Center for an Informed Public have been actively monitoring and collecting data to better understand how certain social media narratives about the conflict have taken shape and spread online.

While research into and analysis of Ukraine-related online narratives will continue for months to come, experts from the CIP have helped research peers, journalists and the public at large make sense of the ways a deadly, distressing and traumatic armed conflict is unfolding in our content feeds.

CIP experts, in a Feb. 24 blog post immediately following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, offered guidance for how to not to contribute to the “fog of war” online: “[C]onsidering the history of this conflict and the countries involved — and in particular the ‘active measures’ playbook of Russia — we can expect an effort to manipulate the ‘collective sensemaking’ process for political purposes. That includes strategically shaping the information space to Russia’s benefit — including using grey propaganda websites, inauthentic social media accounts, and ‘unwitting agents’ to spread disinformation while confusing, deflecting, distracting, and demoralizing information consumers.”

On April 2, when disturbing photos, videos and news reports emerged about scores of civilians killed in the streets of Bucha, Ukraine following the withdrawal of Russian troops from the Kyiv suburb, which international observers and human rights activists have described as war crimes, CIP director Kate Starbird, a UW Human Centered Design & Engineering associate professor who studies misinformation, collective sensemaking and crisis informatics, tweeted: “Expect the horrifying evidence today emerging from Bucha and other areas of Ukraine to be challenged by conspiracy theories who will claim that the images are staged by crisis actors — similar to Sandy Hook, Syria, and so many other horrific events.”

Following Russia’s subsequent false claims that images from Bucha are fake, refuted by satellite images and other evidence, Starbird observed: “It’s the same playbook over and over again. They perpetrate these atrocities purposefully — to punish, threaten, and control. And in parallel they deny them with disinformation campaigns. They sow fear and doubt at the same time. From Syria to Ukraine.”

When Russia made false claims about biological weapons in Ukraine and the dangers of disinformation, CIP faculty member Scott Radnitz, an associate professor at the UW Jackson School of International Studies and director of the UW Ellison Center for East European, Russian and Central Asian Studies, told National Public Radio in an interview: “When it comes to the biolabs, this is an old canard,” noting how the Ukrainian biolabs narrative has been something pushed by Russia since 2011. The biolab narrative “exploded on social media right at the time of the invasion, and it looked like it was quickly picked up by the far right on social media and QAnon promoters,” Radnitz told NPR.

Following a March 14 NBC News report about the resurgence of the biolabs narrative, which started to gain traction online on Feb. 24, Starbird noted in a tweet that the biolabs narrative spread much earlier, sharing an interactive graph of how tweets about biolabs and biological weapons started gaining traction in January before the subsequent larger amplification when Russia invaded Ukraine.

On March 14, Eric Smalley, science and technology editor at The Conversation featured two previous articles written by Radnitz and Starbird as part of an essential reading list to understand the biolabs-related narratives amid the larger framework of Russia’s disinformation and false claims.

In “What are false flag attacks — and did Russia stage any to claim justification for invading Ukraine?,” published in February, Radnitz wrote: “With satellite photos and live video on the ground shared widely and instantly on the internet — and with journalists and armchair sleuths joining intelligence professionals in analyzing the information — it’s difficult to get away with false flag attacks today. And with the prevalence of disinformation campaigns, manufacturing a justification for war doesn’t require the expense or risk of a false flag — let alone an actual attack.”

In “Disinformation campaigns are murky blends of truth, lies and sincere beliefs — lessons from the pandemic,” published in July 2020, Starbird notes “Disinformation has its roots in the practice of dezinformatsiya used by the Soviet Union’s intelligence agencies to attempt to change how people understood and interpreted events in the world,” she writes. “It’s useful to think of disinformation not as a single piece of information or even a single narrative, but as a campaign, a set of actions and narratives produced and spread to deceive for political purpose.”

Radnitz’s expertise on Russia and the post-Soviet world has helped inform understanding of Russia’s current invasion of Ukraine. In a December 2021 Q&A feature with Coda Story, just as Russia was building up its forces on the Ukrainian border, Radnitz shared insights into the complex nature of conspiracies in Russian domestic politics.

“One thing I show in my book is that it’s not simply a matter of the leaders of a country positioning themselves against other countries in order to control the nation,” said Radnitz, the author of the Revealing Schemes: The Politics of Conspiracy in Russia and the Post-Soviet Region (Oxford University Press, 2021). “Often it’s about politicians within a country competing against their domestic opponents. Conspiracy theories are a way of distinguishing oneself from one’s political adversary and creating coalitions within the country. … Political competition also produces incentives for conspiracy theories within the domestic political arena.”

In a March 18 interview with PolitiFact, Radnitz said that while “it’s fair to criticize the Ukrainian government for sharing some misinformation, this is not a fair fight” when considering how “the Putin regime is waging an Orwellian campaign full of propaganda. The two sides are not equally guilty of this, it’s not even a close call. This is really a David and Goliath battle.”

CIP postdoctoral fellow Rachel E. Moran, in a late February interview with Axios noted how the design of visual platforms like TikTok and Instagram don’t give users opportunities to pause and verify the information being shared. And that’s something, Axios noted from its interview with Moran, “made even worse by the emotional climate surrounding a war, which enhances misinformation’s velocity thanks to its shock value or pull on users.”

In a March interview with PolitiFact about the ways misinformers have used a TikTok audio feature to spread fake war footage, CIP research scientist Mike Caulfield noted how TikTok’s platform design makes it challenging for users to pause and reflect on whether information or claims are true, reliable or otherwise warrant additional scrutiny. “The content is often consumed in quick succession, and our critical faculties do better with a bit of a pause,” Caulfield, a digital literacy expert who developed the SIFT method for contextualizing claims online, told PolitiFact.

In a March 15 interview with KUOW Public Radio in Seattle, Caulfield told Soundside host Libby Denkmann that during a crisis event like the war in Ukraine, the demand for information exhausts the supply of reputable information. “People want more information that can be provided through traditional means,” Caulfield said. “It’s a series of events taking place in a foreign country, there are language differences, there are sort of complex political dynamics that the average viewer or reader may not be aware of. And then of course, you know, there’s just the nature of war, propaganda.”

How will the information war about Russia’s invasion of Ukraine change as it drags on? Caulfield has cautioned that there’s a risk that as public attention on the conflict wanes over time, “there could be more attempts to muddle the narrative,” he told The Atlantic’s Charlie Warzel in an interview published March 8.

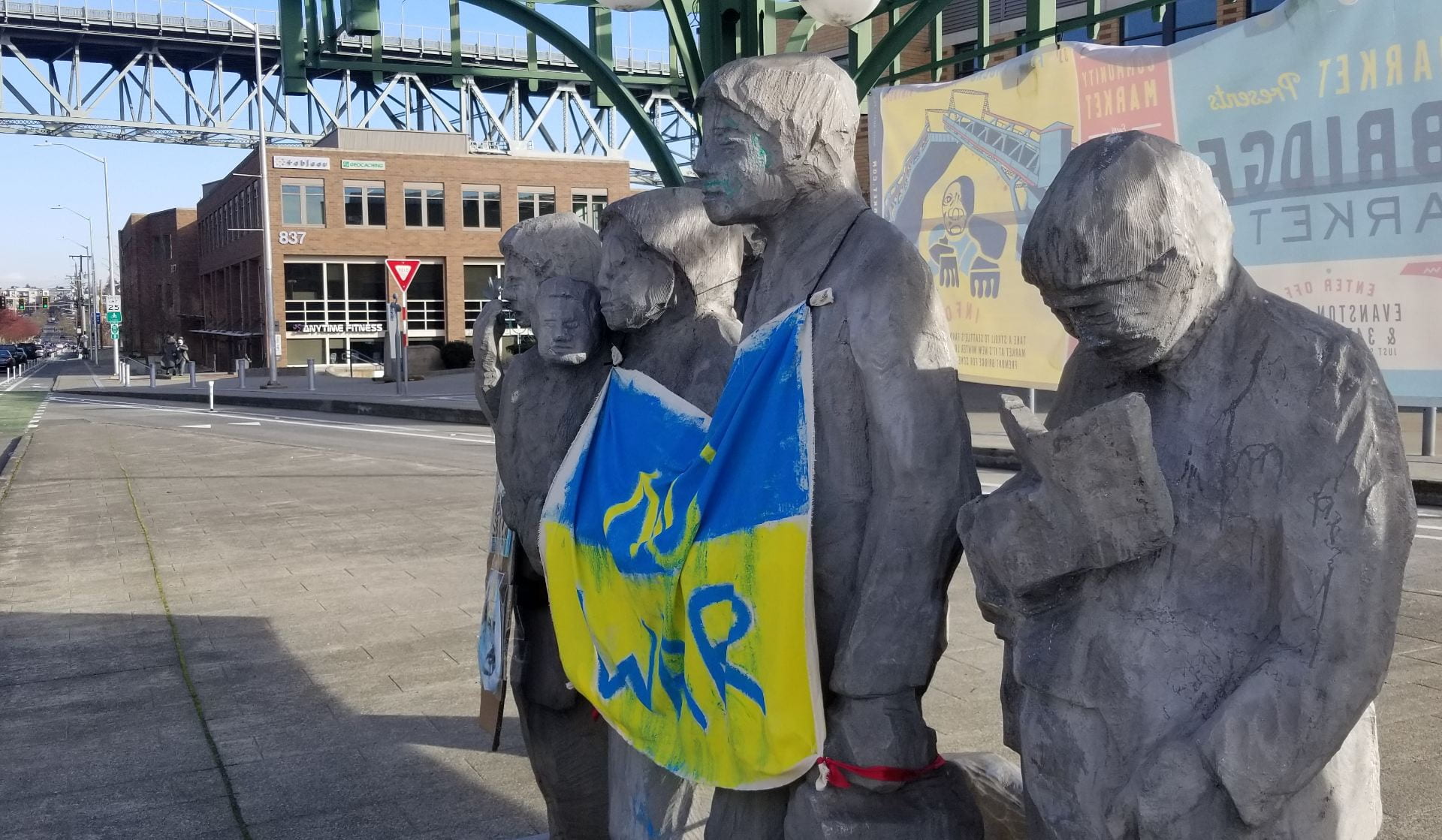

PHOTO (at top): A Ukrainian flag reading “No War” is draped over the Waiting for the Interurban sculpture in Seattle’s Fremont neighborhood.