By Mike Caulfield

UW CIP Research Scientist

There’s a newly released study examining work I did with CIVIX Canada, a civics education organization that is scaling up an impressive curriculum based on SIFT (Stop, Investigate the source, Find better coverage, and Trace claims, quotes and media to the original source) and lateral reading strategies. CIVIX’s study, “The Digital Media Literacy Gap,” was released on Dec. 7 and is available here. Since reading about educational assessments can get a bit wonky, I thought I’d highlight a few important — and promising — findings from work we did in Canadian classrooms.

First, the research context: over the past few years there is a growing research base that supports the belief that a specific type of online media literacy training, based around “lateral reading” methods, can dramatically improve student ability to evaluate information and sources, sometimes with quite small interventions (i.e., a curriculum measured in hours, not months). The core idea of lateral reading is simple — before engaging with content, you need to assess what others think of both the source and claims made. The techniques of lateral reading are not deeply analytical techniques. Stanford University’s Sam Wineburg and Sarah McGrew, in their foundational paper on the subject, described the techniques as quick checks to map out the “unfamiliar terrain” on the web where you’ve landed. In their analogy, a person who parachutes into an unfamiliar forest must start not with thinking about the best route to civilization, but rather, they should start with simpler questions — “Where have I landed? What do the maps tell me?”

That seems obvious, and over time it has become more so. But it’s actually not the way most students approach information online. Online, they tend to judge content through a mixture of bad methods:

- They look at weak signals of credibility from the source itself, such as what the site or individual says about their own credibility. A person who bills herself as a world-renowned medical researcher is seen as a world-renowned medical researcher, and this is not questioned.

- They rely heavily on the appearance of credibility. Are statistics cited? Is the page ad-free? Add a number or two or a footnote, and students will gush about the reliability of the site or post.

- When it comes to claims, they rely heavily on their own intuitions of what is plausible. This is not a bad strategy when the student has a good understanding of a subject. But in practice, this means that assessments are heavily subject to belief bias — a source is seen as credible because its assertions seem plausible, rather than the other way around.

I won’t go into too much detail on this point, but one of the things both Sam Wineburg and I found when we initially looked into this issue was that online media literacy, as it was taught, was reinforcing these behaviors. Students were encouraged (and still are) to focus on surface features of websites (how do they look?) and to ponder whether the arguments presented “make sense” — which, in absence of student domain knowledge, is not much different than asking whether something is intuitively plausible. And sometimes students were encouraged to dig deep and individually verify facts in articles, follow all the footnotes, and so on. That’s not always bad, but in practice it goes very wrong if you don’t ask the important questions first — neither of which deals with your own impressions, but with the impressions of others:

- What have others said about this source?

- What have others said about this claim?

That’s it. If you can’t answer those two questions in a sentence or two, do not pass go, do not collect $200. Behind this strategy is an important insight — the first layer of triage on any idea, source, or claim is social, and the web techniques we teach students should harness the unique features of networked reputation on the web. So rather than lists of 26 questions to ponder about evidence, purpose, layout, ad use and the like, we encouraged students to start by looking up a source in Wikipedia and asking the simple question: “Is this source what I thought it was?” And rather than deeply pondering the plausibility of claims well outside their scope of experience, we encouraged students to do quick Google searches to see if multiple authoritative sources were reporting the same thing.

There was more to it than that, of course. By the time we got to the CIVIX pilot, we had learned all the little ways students go wrong with lateral reading, and worked to address them. The approach at this point is increasingly mature, having gone through many iterations over the past four years.

The CIVIX Study

So, what makes the CIVIX study unique? After all, there have been numerous studies at this point that show that teaching lateral reading works.

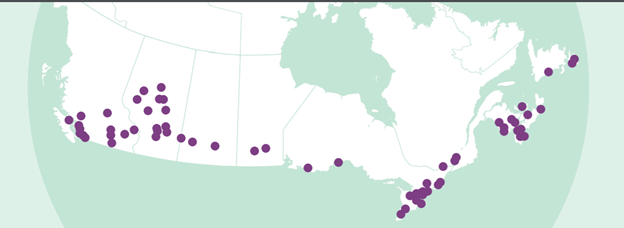

The biggest is scale and breadth. Previous interventions were either small, or confined to a single institution (a cross-institutional pilot for nine universities in 2017 was an exception, but the implementation and testing was not consistent enough to produce publishable data). And scale matters: the world is littered with educational approaches that can succeed in small settings with highly trained individuals overseeing their implementation, but which fail when put to broader use. That’s why of all the graphics in the report, the one that is most striking to me is the map of all the places that participated in the pilot.

Over 70 schools, across multiple provinces representing places with different demographics, different politics and different funding participated. Some lessons were taught online, some blended instruction, and others were conducted face-to-face. It was taught in the middle of a pandemic, between September 2020 and January 2021. Teachers prepared with a two-hour online workshop we designed and an array of support materials. And all of these locations participating in the same pre- and post- assessment of skills.

It’s difficult to organize an educational intervention at this scale, and that’s a place where the experience of CIVIX was invaluable. While relatively new to online media literacy, CIVIX has been running large, cross-institutional educational programs for decades. Their Student Vote program supports over 10,000 schools in Canada engaged in using their unique civic literacy curriculum (they are on the road to supporting another 1,000 in South America, where they are working with Colombian schools). Running a pilot program and managing the assessment of it added difficulties, but the scale of this is truly unique, as is their capability to expand this even further.

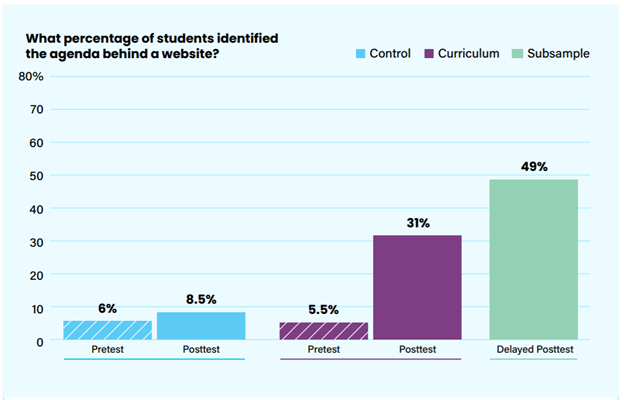

The second notable item is impact. It’s difficult to compare impact across multiple studies — you have different populations, different assessment prompts, different teachers, different cultures. But despite increases in scale, the impacts we saw in this intervention were some of the most dramatic yet. Here’s just one example, of how many students identified the agenda behind a website, with successful application of the skill moving from just 6% in a pretest to 49% in a delayed post-test.

Again, this is a relatively small intervention, but you can see the dramatic improvement in not just student capability, but student habit (the students in the assessments are not told how to assess the source, but simply to go about it how they normally would). And drilling down into what that progress looks like in the free answers (“How did you come to this decision?”) shows we are observing meaningful shifts in how students conceptualize assessing reputation. Here’s one example the report calls out, of what a student succeeding at with the curriculum typically looks like.

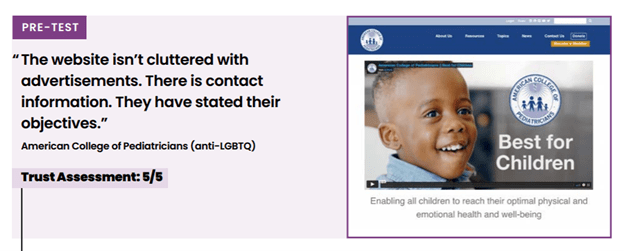

First, we have the pre-test, where the student concludes an anti-LGBTQ advocacy group is a highly trusted source of information on how to deal with juvenile health.

Note that this pattern, which we see repeatedly in our work, undermines the idea that confirmation bias is the overriding reason people make bad judgments on sources. The students here are from a generational cohort that is supportive of LGBTQ rights, and yet they are convinced that this is a strong source of information. Confusion, not motivated reasoning, underlies the error here. Students are under the impression that this small splinter group of physicians is a large, respected, apolitical physician’s organization, and are interpreting their statements through that lens.

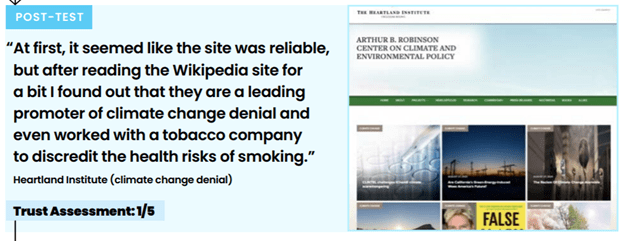

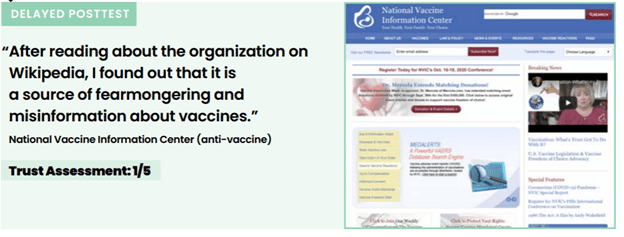

Next, we have the same student after the intervention, this time evaluating an organization associated with climate change denial. And you see here that not only did the student correctly identify that this might be an unreliable source on climate change, but arrived at that conclusion based on more substantial reasons than the number of advertisements on the page. They note what they found during a quick reputation check:

Finally we have an anti-vaccine organization in the delayed post-test many weeks later, to see if the skills stick. And they do:

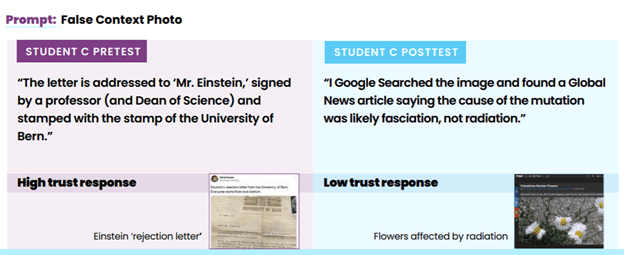

We saw the same pattern across other prompts and students. Here, from the report is a student before the post-test falling for a fake “Rejection letter to Einstein” circulating on the web, because the surface features of it “check out.” Yet, after the intervention they tackle an arguably more difficult prompt on whether a photo of daisies near the Fukushima nuclear disaster is “good evidence” of the effects of radiation there. And again, the shift is not only in accuracy (which one can guess at) but in depth and approach. They move away from relying on their own flawed investigation of the object itself and towards assessing what others say about the claim:

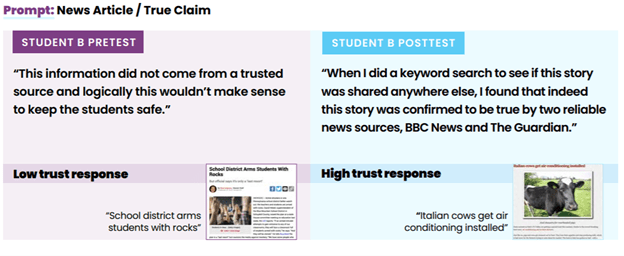

One last example, showing an important point. It’s been suggested in the past that media literacy might breed cynicism — that students are not getting better at discernment but just becoming more suspicious of everything. I think the underlying reasoning captured in the student free responses argues against that. Still, we are always careful in our assessments to balance trustworthy prompts with dubious prompts and make sure that we are testing student ability to recognize the mostly true as much as they can dismiss the mostly false. The following is a set of matched prompts, both true.

In the first, the student comes to the conclusion it is not trustworthy. Why? Because at least to this Canadian high school student, it doesn’t seem plausible that a school administrator in the U.S. would suggest having rocks in the classroom might be a defense against school shooters. After the intervention they are presented with something equally ridiculous — Italian cows are getting air-conditioning and showers installed in their sheds to help them deal with a recent heat wave. But again, what you can see is that this student — like many in the study — radically shifted how they approach information, relying less on their own flawed judgments and instead tapping into the power of the web as a tool to figure out those core questions first — what is the reputation of the source? What is the reputation of the claim? Taking on those questions first, using the quick and flexible strategies we teach them, leads to a better result.

There’s more in the report, or you can contact me at mica42@uw.edu.

Digital literacy expert Mike Caulfield is a research scientist at the University of Washington’s Center for an Informed Public.