A Vietnamese-language version of this blog post is available here: Tiếng Việt

In January, the University of Washington’s Center for an Informed Public announced a new research project “Sending News Back Home: Analyzing the Spread of Misinformation between Vietnam and Diasporic Communities in the 2020 Election,” with initial funding from the Institute for Data, Democracy & Politics (IDDP) at The George Washington University. Led by CIP postdoctoral fellow Rachel E. Moran and UW Information School PhD student Sarah Nguyễn, the project has received an outpouring of insights, supportive emails and personal stories from community members of the Vietnamese diaspora. We were also fortunate to have Nguyễn invited to speak with Saigon Broadcast Television Network (SBTN) about the project. The project was also briefly featured in a recent Vice News article, “The Rise of the ‘Vietnamese Rush Limbaugh.’”

Below is an update of some of our early research findings and how you can read more or participate in this research. We are currently asking for participants for upcoming focus groups on news and information sharing in Vietnamese diasporic communities — more details are included at the end of this post.

Themes from Early Discussions

Over the past few months we have been hosting interviews and informal conversations with academics, organizers and community members across the U.S. and Canada to understand research needs and key concerns of the Vietnamese diasporic community. Several major themes have emerged from these conversations:

- Intergenerational divides: Between generations of Vietnamese peoples (e.g., first to second generations of refugee immigration; grandparents to parents to youth) there exists a disconnect of information and understanding around politics and current events. This means that different generations are exposed to different media outlets and information sources, which makes having conversations about news and current affairs even more complicated. In tackling the spread of misinformation we have to find ways to facilitate conversations across these separate media and information diets.

- Cultural dimensions: There are distinct historical and contextual understandings of the meanings of political terms and phrases — e.g., “socialist,” “communist,” “relationships with China,” and general U.S. political infrastructure. Differences in these understandings allow “sticky” misinformation narratives around candidates being “socialists”, or foreign interference in the U.S. election, to gain traction.

- Power dimensions: Vietnamese-Americans are a growing political power in the U.S. and community members fear that misinformation and distrust in news media could undermine efforts to increase political involvement and representation. We are also seeing examples of political disinformation being targeted at minority communities in the U.S. — for instance with Spanish-language misinformation spreading in Latino communities around the U.S. election. There are therefore concerns that Vietnamese Americans could be a target for ideological disinformation to take advantage of their increasing political presence.

- Language barriers: As highlighted by Terry Nguyen’s work, the “language diversity within the AAPI community means misinformation is difficult to track.” Misinformation continues to thrive because it is available in Vietnamese on social media. Further, well-researched information from traditional journalism (including Vietnamese-language news outlets in the U.S.) is less readily available due to costs of translation and the closing down of local/grassroots news outlets.

- Social media platforms: Social media platforms (e.g., Facebook, WeChat, Telegram, YouTube, etc.) are not doing enough to slow the tide of misinformation that is not in English. The majority of Vietnamese-language posts in our datasets from Facebook and YouTube contain misinformation that has not been labelled by the platforms (yet the same narratives are labelled on English-language posts). This is not just an issue within the Vietnamese community, but exposes the lack of investment technology platforms are making in content moderation of non-English content.

Collection of Social Media Data

To better understand how social media platforms are shaping the flow of misinformation, we have begun collecting data around key 2020 election narratives on social media including things like voter fraud, ballot stealing and foreign intervention. Our Facebook database, alone, contains over 4,000 Facebook posts with over half a million interactions. We have also collected videos and their accompanying metadata from 27 YouTube channels with over 10,500 videos total that have been recommended by community members to hold problematic information. A number of these YouTube channels have more than 100,000 subscribers.

We will use these posts and videos to identify misinformation and look to;

- Understand what stories were the most popular and widely shared.

- Identify key actors and accounts involved in spreading misinformation.

- Survey whether social media platforms tagged election-related content (as they committed to doing).

Call for Participation

We will be conducting focus group discussions with community members to explore the different kinds of news that people faced during the 2020 election period. These focus groups will include 4 to 5 people who identify as members of the Vietnamese diaspora. In these small group settings we hope that community members will feel comfortable to share their experiences and discuss how they find trustworthy information. All sessions will be hosted in both English and Vietnamese.

We are looking for participants! If you or someone you know would like to chat with us please sign up here.

If you have any questions, feedback, or interest in getting involved with the research process/product, please feel free to get in touch with Dr. Rachel Moran (remoran@uw.edu) and Sarah Nguyễn (snguye@uw.edu).

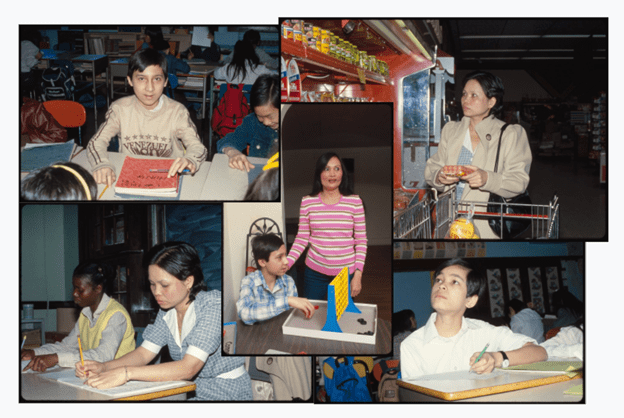

Image at top: A collage of Library of Congress archival photos of Vietnamese children of American G.I.s in Rochester, New York.