By Michael Grass

More than 1,000 middle and high school students, teachers and educators from across Washington state and the nation participated in MisinfoDay 2021, a series of virtual workshops on March 18 where facilitators explored strategies for spotting misinformation, fact-checking claims and sources, better understanding the landscape of information disorder and the goals and tactics used by those who spread disinformation.

MisinfoDay, first hosted by the University of Washington Information School in March 2019, is now organized and presented in partnership with UW’s Center for an Informed Public and Washington State University’s Edward R. Murrow College of Communication. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, last year’s planned in-person MisinfoDay event was cancelled, but with an all-virtual format for 2021, the misinformation awareness and educational programming from this year’s MisinfoDay reached a wider audience, including more than 1,000 students and educators across Washington and other states, including Florida, Georgia, Illinois, New Jersey, Oregon, Tennessee and South Carolina.

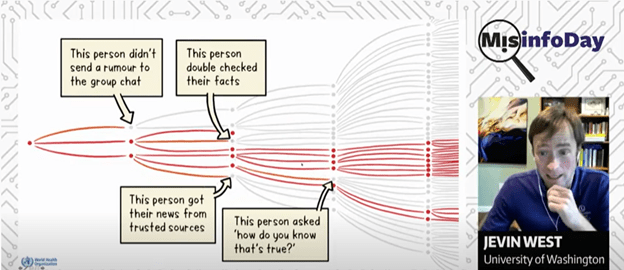

Center for an Informed Public director Jevin West shares a World Health Organization infographic showing how misinformation can quickly spread during a MisinfoDay 2021 workshop.

“Nothing is more important than having us, all of us, on the internet not share” false and misleading content as much as possible, said CIP director Jevin West, an associate professor at the UW iSchool, during his Spotting Misinformation workshop. “We always say ‘Think more, share less,’” West said, showing a World Health Organization infographic showing how misinformation can quickly spread. “If we do a little less sharing and a little more thinking, we can truly start having an effect” on curbing mis- and disinformation online.

Amid the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic and other tumultuous events — including the 2020 U.S. elections and the mob violence at the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6 — that have brought uncertainty and confusion to our information environments, educators and others have been acutely interested in how they can improve information literacy, fact-checking skills and classroom lessons to better prepare students and others to resist mis- and disinformation. While each of the MisinfoDay 2021 workshops was chock-full of important insights and lessons, here are a few key highlights and takeaways from this year’s program.

Mis- and Disinformation Is Often Built Around a ‘Kernel of Truth’

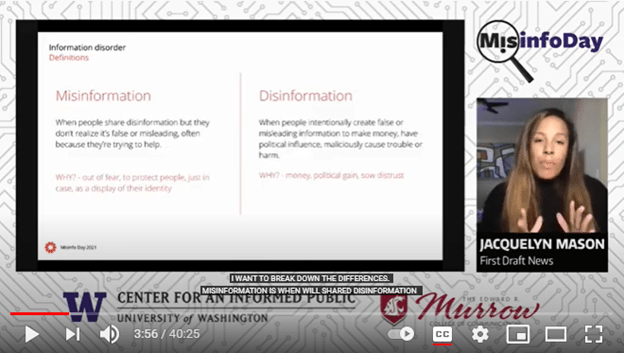

As part of her workshop on Understanding the Landscape of Information Disorder, First Draft News senior investigative researcher and special projects manager Jacquelyn Mason discussed seven different types of mis- and disinformation: satire or parody, false connection, misleading content, false context, imposter content, manipulated content, and fabricated content. Mason explained that one of the reasons why misinformation can sometimes be hard to identify is that “a lot of misinformation has a kernel of truth” that may make it seem accurate or legitimate at first glance.

Jacquelyn Mason of First Draft News explains the difference between misinformation and disinformation during MisinfoDay 2021.

That was something echoed in a separate MisinfoDay Disinformation Goals & Tactics workshop co-facilitated by CIP co-founder Kate Starbird, an associate professor in the UW Department of Human Centered Design & Engineering, and CIP postdoctoral fellow Kolina Koltai. Just like misinformation, which is false information that’s unintentionally shared, disinformation, which is false information intended to mislead or deceive, is often built around those kernels of truth. But disinformation is also “layered with distortions or exaggerations” and can function as part of a campaign involving other pieces of information that, Starbird said, can “work together to create a false perception” around an event, policy issue, individual, group or organization.

For those reasons, Starbird said, disinformation can be harder to detect, since you can’t “simply fact check one piece of information” to figure out what’s real and what’s false or misleading.

Everyone Is Responsible for the Information They Share

During a Fact-Checking Claims and Sources workshop, Scott Leadingham, a news manager at Northwest Public Broadcasting and former education director at the Society of Professional Journalists, discussed some of the important principles in journalism around fact-checking, vetting sources and making sure the information that reporters and news organizations share and publish is accurate.

But Leadingham also stressed to students that “everyone is responsible for the information they share — not just journalists, but you are included in that.”

Scott Leadingham, news manager at Northwest Public Broadcasting, faciliates a fact-checking claims and sources workshop during MisinfoDay 2021.

In her workshop, Starbird said that one of the most important things information consumers and social media users of any age can do is “slow down and reflect on things before you share.”

In fact, when you encounter information that may raise questions about its sourcing, legitimacy or accuracy, you should first “Stop.” According to Michael Caulfield, a digital literacy expert at WSU Vancouver and MisinfoDay 2021 workshop facilitator, that’s the “S” in a fact-checking method he developed called SIFT.

“Ask yourself,” Caulfield said during the Fact-Checking Claims and Sources workshop with Leadingham: “Do you know who is sharing this? Do you know why you trust them? Do you know who they are at all or what the connection to the subject is? Do you know anything about the claim? Are you an expert in this? Do you have what we call ‘domain knowledge’ in it?”

If not, Caulfield said, you should be wary about immediately sharing it and instead should proceed with the other letters in the SIFT method: “I” (Investigate the source), “F” (Find better coverage) and “T” (Trace claims, quotes and media to the original context).

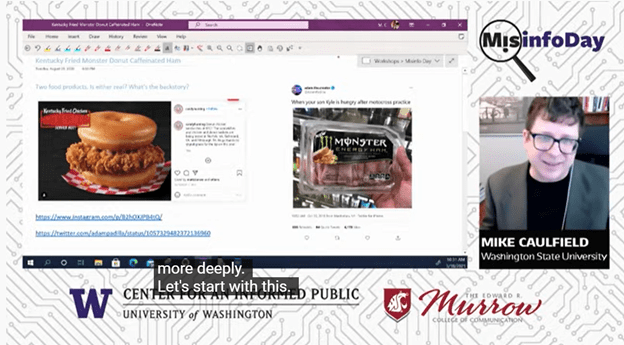

Michael Caulfield, a WSU Vancouver digital literacy expert, walks MisinfoDay 2021 participants through a process to factcheck examples of viral photos to tell if they’re real or fake.

As an example, Caulfield walked students through steps he took to assess whether two viral photos that were shared online — one showing a KFC fried chicken sandwich that used glazed donuts in place of buns and the other of a social media post with someone purporting to find a Monster Energy-branded caffeinated ham product in a grocery store’s deli section — were real or fake. As Caulfield demonstrated, while the fried chicken sandwich with donuts was in fact part of a real KFC promotion and was written about by legitimate, credible news sources, like USA Today, searching for additional information about the caffeinated ham turned up a trusted fact-checking website, Snopes.com, that had debunked the photo as a hoax, along with news organizations that investigated and made the same determination.

Taking responsibility for the information that people share on social media and elsewhere online also includes the responsibility to correct mistakes and clarify points of confusion to prevent additional spread of mis- and disinformation.

Starbird said it’s important to “understand that everyone makes mistakes. We’re all vulnerable to mis- and disinformation. The most important thing is that we learn to recognize it and correct it.”

Avoid Being an ‘Unwitting Agent’ That Spreads Disinformation

Kate Starbird, a Center for an Informed Public cofounder and associate professor in the UW Department of Human Centered Design & Engineering, during a MisinfoDay 2021 workshop.

During her workshop, Starbird discussed how disinformation relies on others to be “unwitting agents” to spread their false or misleading information. That’s especially true during elections.

“When we’re politically motivated, we can become unwitting agents of disinformation campaigns,” Starbird said.

During the 2020 U.S. elections, disinformation researchers like Starbird found that “people were primed to be receptive to false narratives of voter fraud … and in some cases misinterpreted real-world events to bring them into alignment with these false and misleading narratives. So they were spreading false information without even realizing it.”

For people involved in these kinds of misleading and deceptive information campaigns, there’s usually some kind of goal in mind, motivated by politics, ideology or financial interest.

Jordan Foley, assistant professor at WSU Murrow College, facilitates a workshop on disinformation goals and tactics during MisinfoDay 2021.

Jordan Foley, an assistant professor at WSU’s Murrow College, said during his Disinformation Goals & Tactics workshop that those who create and seed disinformation campaigns often seek out “breaking news or active political crises or places on the internet where there are data voids.”

Creators of disinformation, Foley said, often target places online “where prejudice, in-group/out-group animas, racial, ethinic and gender divisions are really high.” These are places where disinformation tries to gain a foothold and traction to spread further.

While fact-checking individual pieces of information is vitally important, Starbird also recommended that students “tune into their emotions” when they’re considering sharing something they come across online. “When we look at people who spread disinformation, it’s often because they were emotionally activated,” she said. “They feel outrage or anger or self righteousness. So tune into your emotions to ensure you’re not being manipulated.”

Respond to Mis- and Disinformation With Empathy

One of the common questions mis- and disinformation researchers get from the public is how they should respond when a friend, family member or colleague shares mis- and disinformation. During workshop Q&As, this concern resonated among many participants who submitted questions.

“This is a tough one,” Mason said, “because we love our friends and family.” The challenge is that pushing back against mis- and disinformation can cause some people to dig in their heels.

“If you see your friends and family sharing mis- and disinformation online, don’t confront them in a public forum,” Mason said. “Nobody wants to be embarrassed or humiliated. Usually, that’s the point where they double down and they retreat into their conspiratorial circles or content.”

It’s important to respond with empathy and first to respond privately. “Give them some evidence of where they can find the correct information and say ‘hey, you might want to take this down or add a note’ to say this was corrected,” Starbird said, who noted that everyone makes mistakes, even mis- and disinformation researchers.

Center for an Informed Public postdoctoral fellow Kolina Koltai, who researches vaccine misinformation, faciliates a MisinfoDay 2021 workshop.

“Definitely telling them that they’re wrong is never the way to convince someone that they are actually wrong,” said Koltai, who researches vaccine-related misinformation. While it can be difficult to discuss some hot topics like politics with friends and loved ones who share false claims or misleading content, “it’s worth trying to engage that person, not always in that public sphere, but in that private sphere.”

And it might end up being a longer-term conversation, Koltai said during a Disinformation Goals & Tactics workshop. “Something that’s important to remember with some of these topics is that when people have very well-formed opinions about something that’s based on misinformation, it wasn’t just one piece of misinformation or content that got them there. It was a collation of lots of misinformation. It’s never necessarily going to be one bit of correct information that gets them out of it.”

But these difficult conversations often start with trying to find a place of common ground or shared understanding and going from there.

Overall, Starbird said, “we all want to be better” information consumers, “so let’s help each other create a healthier information environment.”

MisinfoDay 2021 Resources

- LEARN MORE ABOUT MISINFODAY 2021

- DOWNLOAD THE MISINFODAY 2021 TOOLKIT

- WORKSHOP RECORDING | Understanding the Landscape of Information Disorder with Jacquelyn Mason

- WORKSHOP RECORDING | Fact-checking Claims and Sources with Mike Caulfield and Scott Leadingham

- WORKSHOP RECORDING| Spotting Misinformation with Jevin West

- WORKSHOP RECORDING | Disinformation Goals & Tactics with Kate Starbird and Kolina Koltai

- WORKSHOP RECORDING | Disinformation Goals & Tactics with Jordan Foley